McCloy sets the scene for his trip up the spine of England at its beginning at Edale: grey, leaden skies that turn to rain. The route has a reputation for being a demanding and sometimes menacing prospect.

This is an account of his walk along the country’s first long-distance trail, its history, the people who live and work along it and those who visit it.

It sets out the historical background to the first hill encountered, Kinder Scout, and the importance of its place in the fight for outdoor access. The author quotes some interesting figures for the number of walkers who give up their own fight to complete the Pennine Way shortly after passing over Kinder Scout. This, he points out, can possibly be due to the physiological changes that take place on a long, arduous walk, when blood sugars drop and depression can result.

The good news is, if you make it to Malham in the Yorkshire Dales, it’s likely your body will have adapted and you have a better chance of making it to the end in the Scottish Borders.

The book is not a guidebook. Rather, it’s a mix of McCloy’s personal experiences on the way, and the fruits of lots of subsequent research and interviews. There are a few niggly factual errors: he says the Four Inns Walk, a challenge event through the Peak District, starts at the site of the old Isle of Skye Inn. It doesn’t; it starts at Holmbridge – I know, I’ve done it. He also says Pen-y-ghent’s name is Welsh, though most would say it’s Cumbric, an old British language akin to Welsh, but spoken in what is now northern England and southern Scotland. Small points, but niggly to pedants.

Tom Stephenson figures often in the pages of the book. His Daily Herald piece in the 1930s in which he argued England should have its own version of the USA’s Appalachian Trail was the inspiration for the Pennine Way and he is viewed by many as the father of the route.

The author reveals that, before its instigation, a group of MPs undertook a three-day walk along part of the planned course – hard to imagine parliamentarians doing the same now. He also points out the dogged opposition to the idea by many of the water boards along the route, fearful, they said, of their water’s purity if the great unwashed were allowed on to their hallowed ground.

McCloy interviews many people for the book, from welcoming and unwelcoming B&B landladies to the owners of the renowned Pen-y-ghent Cafe. Also interviewed post-walk is Heather Procter, Pennine national trails manager, who checks all the gates, stiles and direction signs along her patch.

She reveals an interesting fact: the oft-quoted distance of 268 miles is probably not the one covered by most Pennine Way walkers. To do this distance, you would have to undertake all the optional loops and indeed both alternative routes near the end of the trail. She says most will actually walk about 253 miles.

There’s a discussion by McCloy of whether the route’s popularity is in decline. Alfred Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk, shorter at 192 miles and covering a more varied terrain, is increasingly popular and seen by many as a preferable alternative. Wainwright was no huge fan of the Pennine Way, despite writing his companion guide to the route. For years, the proceeds of the book were used to pay for a pint of beer at the Border Hotel for those who completed the distance, a tradition that ended in the years after his death. Happily, a local brewery has stepped in and a pint is again on offer to those who walk the whole route.

There’s plenty of colour in this book, with tales of youth hostel days when the way was in its infancy, including a one-legged warden with cats all named after Roman emperors, plus a stuffed stag’s head with a cigarette permanently stuffed in its mouth.

The format of the chapters is to include journal-type accounts, expanded with factual diversions, which almost suggest the author’s thoughts as he plods along the Pennine Way miles. There’s also a good flavour of the achievement felt by those who complete this demanding challenge.

McCloy says: “Arguably, there is no better time to walk the Pennine Way than the present.” It’s less crowded and better maintained than during most of its history. But therein also lies a problem for a book such as this. With numbers of Pennine Way walkers nowhere near what they once were, is there a big enough audience for this publication?

Who will buy The Pennine Way: the Path, the People, the Journey? This is not, as I said, a turn-by-turn guidebook, but rather and account of the journey, with lots of added factual research, interviews and even some philosophy, though nothing too deep. The writing is colloquial and unflowery, and it’s an easy read.

It will appeal to anyone contemplating tackling England’s oldest national trail who appreciate some background and detail about the people and places they may encounter, and probably to those who have done it and will nod in recognition of the descriptions.

Who knows, Andrew McCloy might just prompt a few more people to pull on their boots and head to Edale – or Kirk Yetholm.

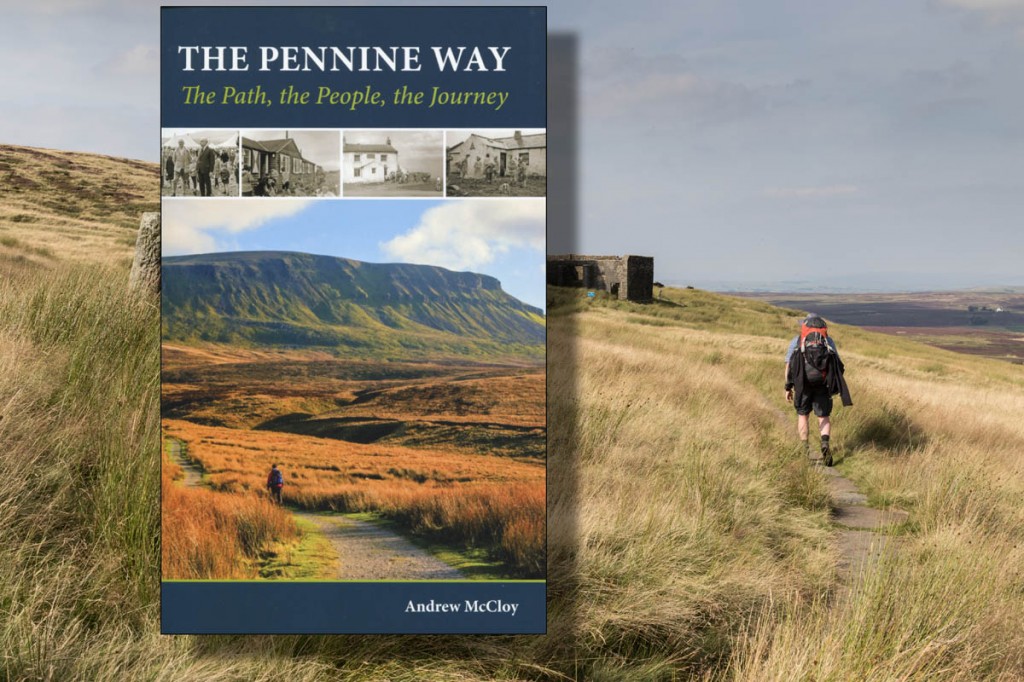

The Pennine Way: the Path, the People, the Journey, by Andrew McCloy, published by Cicerone, £12.95.