The death zone is generally held to start about 8,000m up, where the atmosphere is so thin, the protection from solar radiation so sparse, that each hour spent there means you die a little.

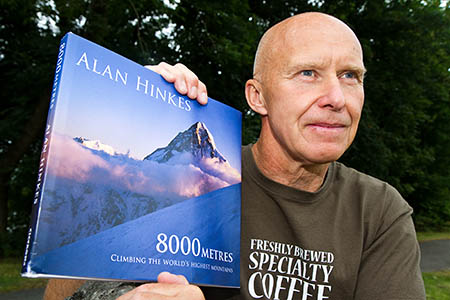

There are 14 peaks whose summits rise above the magic 8,000m mark, and only one Briton has climbed them all: Alan Hinkes.

This book, published today, is a labour of love charting the highs and lows of this remarkable feat, which took the Yorkshire mountaineer 18 years to achieve.

Fortunately for us, Hinkes had the presence of mind to take his camera with him on all his ascents and, more importantly, capture photographs when many other climbers would simply have been concentrating on not slipping to their death.

This well produced coffee-table book contains dozens of images of the remote, dangerous world of the high Himalaya and Karakorum.

Although the photographs will probably be the first thing readers leaf through, there is also a wealth of insight into the sometimes terrifying conditions on the world’s highest mountains.

Anyone reading Hinkes’s book who has met the man will agree with fellow Yorkshireman Brian Blessed’s statement in his foreword that: “Alan writes as he talks, with passion and simplicity.”

Hinkes never set out to become the first and so far only Briton to summit all the 8,000m peaks. He says in the book: “Once I had knocked eight of them off, I decided to go for the final six.”

His style echoes that of another blunt mountaineer, Sir Edmund Hillary who is reported to have said after his Everest triumph: “We knocked the bastard off.”

Hinkes won’t win any literary prizes for flowery prose, but his accounts of each summit are detailed and give an insight into his motivations and approach to tackling these extraordinary acts.

While, as in all mountaineering books, death is never far away, with corpses passed on the way to many summits, Hinkes’s approach is that a summit attempt is not worth dying for. In fact, he is obsessive about not even suffering frostbite, always careful to take his boots off and rub the circulation back into his cold toes. ‘No mountain is worth a digit’, he says.

Once or twice he has teetered on the brink of what he calls the ‘incident pit’: the feeling that circumstances are ganging up on you to drag you into an inescapable crater that will inexorably draw you to death.

He has turned back within the summit of peaks, notably his final one Kanchenjunga, within sight of the summit.

Rather than a national flag, he takes a picture of his daughter and later grandchildren to each summit. All part of the assured Hinkes philosophy: “No mountain is worth a life; coming back is success and the summit is a bonus.”

Alan Hinkes on Shishapangma: climbing Alpine-style mean carrying large rucksacks. Photo: Alan Hinkes

The Yorkshire climber, who cut his teeth first on Roseberry Topping, which gets a little chapter to itself, recounts the notorious sneezing incident on Nanga Parbat when a prolapsed disc was the result of an unfortunate encounter with a chapatti.

And he describes the difficulty of wandering for half an hour round the cloud-encompassed summit plateau of Cho Oyu which he says was a little like a Cairngorm hilltop only bigger, trying to find the highest point. Hinkes is clear in his mind he found it; others have doubted his success. As he told me in July: ““There is no controversy as far as I’m concerned. I’ve done them all.”

He likens the completion of the 14 8,000ers to the mountaineering equivalent of the four-minute mile in athletics. But, he says, more than a thousand people have run a sub-four-minute mile; only 30 people have climbed all 14 highest mountains.

His photographs get the true coffee-book treatment and there are some remarkable images of this strange environment.

Happily, there are no images of the time he had to be rescued wearing only his underpants after being avalanched in his tent.

There are some intriguing pictures too: Hinkes heading up Lhotse clutching an ice-axe in his left hand and a plastic carrier bag – essential mountaineering gear – in the other.

And his picture of the snow-free Dhaulagiri summit, scoured down to the rock by jetstream winds, will look curiously familiar to walkers who take to the Lake District hills or Scottish peaks. Except, of course, it’s 23,000ft higher!

Each ascent is given a separate chapter in the book, and there are also supplementary sections on topics as varied as chapatti and chips; dealing with death, and the trek in.

It took the Yorkshireman 27 expeditions and 18 years to ‘knock off’ the world’s 8,000m mountains and this book is the culmination of another eight years’ writing and sifting of photographs when he wasn’t ‘playing out’.

It’s a unique collection of images and facts from a man who, fortunately, is not just a mountaineer, but a photographer too.

And, like all good yarns, his chapter on his final peak Kanchenjunga is a nail-biting epic.

Having completed the round, Hinkes says he is ‘free simply to enjoy the hills’ and we are free, as armchair mountaineers, to join his adventures vicariously with the coffee table at our sides.

Alan Hinkes

8000 Metres – Climbing the World’s Highest Mountains

Cicerone Press

£25