The Lakes poets are credited with turning a hitherto disregarded wild area of England into a honeypot for tourists.

The romantic writings of William Wordsworth, Robert Southey and Samuel Taylor Coleridge are renowned for their descriptions, among other things, of the beauty of the Lake District. Should we now add another name: Alfred Wainwright?

It may seem fanciful that an author of, essentially, a set of illustrated guides to walking the fells should be included in this roll-call of celebrated Lake District authors, but it is a question posed by the publication of a book of Wainwright’s letters.

Journalist and writer Hunter Davies, Wainwright’s biographer, spent 17 years rooting out correspondence from the writer of the Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells, and even found a stash of hitherto unpublished letters in the loft of his Kendal home after his death.

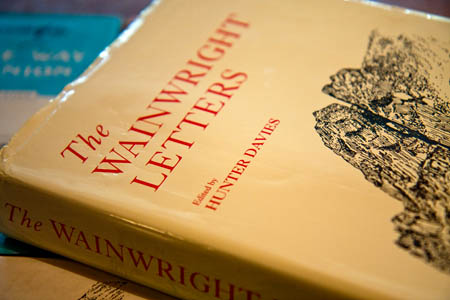

The result is The Wainwright Letters, a collection of 343 pieces of correspondence ranging from the banal to the romantic; angry to sarcastic; humorous to near obscene.

The work gives a new insight into a controversial character who divides many outdoor enthusiasts’ views. Aficionados will barely have a word said against Wainwright; others don’t get the point of his work.

It is difficult to know whether, when writing to a former workmate Lawrence Wolstenholme, he has his tongue in his cheek. He tells Mr Wolstenholme: “Unquestionably, I am the best writer in Kendal.” And to another former worker at Blackburn Town Hall, Eric Maudsley, he says: “Future generations, when they think of Wordsworth and Southey and Coleridge and de Quincey, will think of Wainwright also.”

What is inescapable is that the man viewed as a cantankerous solitary wanderer on the fells left a huge volume of work. The Wainwright Letters lists 61 of his own works, along with contributions to authors such as Richard Adams in The Plague Dogs, and children’s books by his long-time correspondent Molly Lefebure.

It is evident that, while the public perception of Wainwright is of a taciturn and diffident man ill at ease in strangers’ company, he used his writing to convey his feelings. His pen and typewriter were the means by which he felt best able to express himself.

And express himself he does in plenty. It will come as a surprise to many just how explicit Wainwright could be. The unlikely surroundings of the municipal offices in Blackburn appear as a maelstrom of sexual tension, flirting and, indeed carnal activity.

He certainly dwells, in his early letters, as much on the shapely form of his female colleagues and acquaintances as on that of the wonders of the Lake District’s hills and valleys. Was he a fantasist or a philanderer?

He boasts: “I have become a favourite with the ladies! And I like it a lot. Nowadays, I never spend a night moping and sighing: the trouble is to resist all the invitations I get for a night out.”

And later: “I am carrying on affairs with half-a-dozen women, all of whom are ready to lie down with me when I give the word.”

Ruth, his wife, barely gets a mention until his description of divorce proceedings much later in life. Writing to Mr Maudsley, he lists a variety of topics such as parenthood and the Lake District. Under ‘married life’ is a blank space.

The theorem is that the written work of Wainwright is the result of his unhappy marriage, a problem he shared with Coleridge who eventually, like the fellwanderer, separated from his spouse.

It is possible his early excursions to the countryside were as much an excuse to be in female company as an opportunity to enjoy the landscape. The Pendle Club, a walking association he formed, seems as much a meeting place for pleasures of the flesh as for wholesome country rambles.

His move to a much smaller municipal office in Kendal in October 1941 seems to engender a Damascene conversion, however. Wolstenholme learns from Wainwright: “All those unhealthy tendencies I have shed as easily as a garment. They were quite superficial. Believe me, your remarks about ‘hillocks’ and ‘valleys’ doubtless intended to tantalise me, arouse no feeling whatever. Blue-veined milky bosoms interest me not at all.”

Two years after his move north, he reveals he has begun what would become the celebrated guidebooks, though he sees himself initially principally as an illustrator. The pictures come first; the words second.

His first Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells was published in 1955 under the name of Kendal librarian Henry Marshall, a fiction he continued for some time to protect his municipal position as borough treasurer.

Famous names crop up in his letters. Walter Poucher, the perfumed author of a set of photographic mountain guides, writes a letter of appreciation; Harry Griffin, the Cumbrian outdoors writer and founder of the Coniston Tigers, seems to be mainly a target of Wainwright’s sarcasm; and Dalesman editor Bill Mitchell appears never to hit it off, failing to get much usable material from his meetings with the author.

There is evidence of Wainwright’s sardonic wit throughout the letters and perhaps this is the true nature of the man: his diffidence masks an underlying humour mistaken for aloofness and arrogance.

Len Chadwick, one of the four researchers who helped Wainwright with his Pennine Way Companion, receives an unrequested cheque for his expenses with a note telling him: “Payments need not be accounted for; if there is any balance it may be spent in riotous living with AW’s compliments.”

He is certainly generous financially and supported for many years an animal shelter in Cumbria from his royalties, a position HM Inspector of Taxes seemed hard-pushed to understand.

Betty McNally, the cultured woman of his dreams first imagined in his pre-war account of his ‘long walk’ A Pennine Journey, appears in his Kendal workplace for an official admonishment over an unpaid bill, and he is smitten.

His letters to her are the most intimate and his infatuation is almost schoolboyish in nature. Ruth finally files for divorce, yet incredibly agrees to return to the marital home once a week to do the washing for the domestically incapable Wainwright.

She eventually divorces him on the grounds of mental cruelty and he marries Betty, a lover of the hills like him, in March 1970.

Plans for a guidebook to the Offa’s Dike path and Walking the Border never come to fruition but the famed Coast to Coast Walk is a product of his later years.

Chris Jesty, who would go on to write updated versions of his Pictorial Guides, is told this must wait until after Wainwright’s death to revise the books, though he teases Jesty that he was only 82 and might live for another 20 years. But by 1984, macular degeneration has all but destroyed his eyesight and he is unable to continue his illustrations. He tells Ron Scholes in December 1985: “I am obviously nearing the end of the road.”

Wainwright died in January 1991, three days after his 84th birthday.

Whether he will indeed be remembered by future generations in the same way as the 19th century romantic writers is open to question. His range is narrower, though no less interesting to outdoors enthusiasts, of whom there is a growing number.

The Wainwright Letters provides a further insight, after Hunter Davies’s original biography, of the man viewed as the epitome of a taciturn solitary figure on the fells. It is manna from heaven for aficionados and will provide food for thought for those less sure of Wainwright’s stature.

Each group of letters has either an introduction or a note at the end by Davies, to put the letters in context.

One irritation is a number of literals in the typeset letters. It is not clear whether these are Wainwright’s or Davies’s. Mr Davies says: “I have left unchanged Wainwright’s spelling, grammar and underlinings, but now and again have rationalised his punctuation, to make things flow.”

However, it is clear at least one error that is clearly down to the editor: Davies calls the Scottish 3,000-footers the ‘Monros’ whereas on the same page Wainwright describes them as ‘Munroes’. It would be useful, in a collection of letters from a man as punctilious as Wainwright, to have this clarified.

The Wainwright Letters, edited by Hunter Davies, is published by Frances Lincoln.

£20.00