Ever since George Mallory’s 1924 justification for attempting Everest with the now immortal words “Because it’s there”, mountaineers have devised a plethora of reasons for aiming high in their climbing aspirations.

Altitude is the obvious draw: Everest has become the target of so many climbers not because it presents any particular technical challenges – the earth’s second highest mountain K2 is a much harder climbing prospect – but simply because, at 8,848m (29,029ft), those boots on its summit ice will not be surpassed in height by any other on our planet.

Geography comes into baggers’ targets too. From the simple desire of charity one-day mountaineers to knock off Scotland’s, England’s and Wales’s top peaks in a day to the more esoteric desire of Yorkshire climber Alan Hinkes to visit the shire county tops in record time – the location of the hill is the key to list tickers not just in Britain but across our globe in aiming for the top.

Hence the popularity of the Seven Summits. As with all hill lists, there is an element of contention in what constitute the highest points on the earth’s seven continents. Even the number of continents is open to question – some maintaining there are only five true ones.

However, some 275 men and women are reckoned to have climbed the Seven Summits according to one or other version of the list. A brief explanation of the variants: the original list, postulated by American climber Richard Bass was: Everest, highest in Asia; the Vinson Massif in Antarctica; Kilimanjaro in Africa; Aconcagua in South America; Denali (Mount McKinley) in North America; Elbrus in Europe; and Kosciuszko in Australasia.

Even this list wasn’t without controversy, some pointing out that with Elbrus being on the border between Asia and Europe, the true European crown should be worn by Mont Blanc in the Alps.

Then Reinhold Messner, the great Italian alpinist, suggested Indonesia’s Puncak Jaya or Carstensz Pyramid as a better contender for the highest peak in Australasia and certainly a more strenuous prospect than the relatively simple amble up the 2,228m (7,310ft) Kosciuszko.

Whichever list the Seven Summiteer subscribes to, it is a fact that fewer than 300 human beings have completed one or other version of the continental tick-list.

But now, there is a new Seven Summits list that, with some confidence, I can predict no-one alive will achieve. Perhaps their grandchildren or great-grandchildren may start the quest, but for now the list postulated by Alasdair Wilkins in his Rough Guide to Solar System Mountaineering on science and futurology site io9 is way beyond even Leo Houlding, Reinhold Messner or Alan Hinkes.

Baffin Island’s Asgard may have presented Mr Houlding and his team with a huge technical challenge, with constant rockfalls, freezing fingers and hold-less rock; and chapatti flour almost deprived Alan of his 8,000m triumph, but the Solar System Seven are worlds apart – literally.

The mountaineer of the future will face lethal radiation levels, clouds of sulphuric acid and temperatures as low as –200C and as high as 600C. He or she will also need some very rich expedition sponsors.

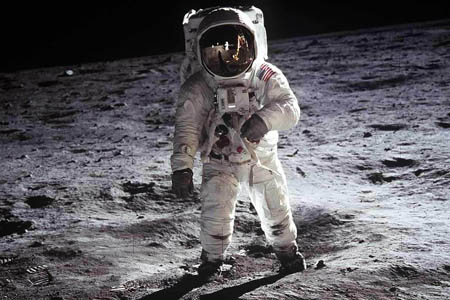

As a warm up for tackling the Solar System’s top peaks, Wilkins suggests a trip to the moon, bearing in mind lunar tourists who want a quick orbit will be looking at a bill of about £125m, so a trip round those altruistic benefactors is going to be a prerequisite.

Then there’s the gear. Those thick astronauts’ gloves aren’t going to be much use when grappling with the routes on the 4,700m (15,420ft) tall Mons Huygens, the lunar high point.

And forget supplementary oxygen – you’ll need to take all your own, or mine the polar water and break down the H20 into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen for fuel.

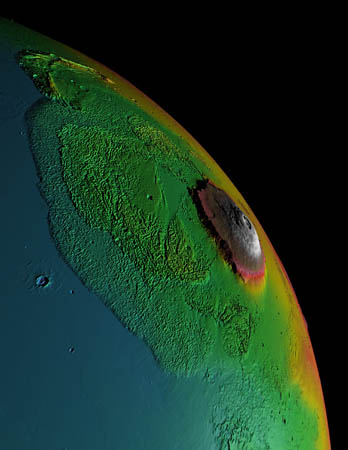

Beyond the moon, the difficulties for the space climber really start. Olympus Mons, Mars’s tallest peak, is also the biggest in the Solar System at 27,000m (88,583ft) – three times as high as Everest. The good news is that the ascent would be a gentle stroll up a gradual slope. But allow yourself plenty of time – the caldera of this volcano alone is 85km (53 miles) wide.

And pack your thermals: average temperature is a cool –63C.

Having topped out on the red planet’s highest peak, things start to hot up for the space climber. Mercury’s surface is largely uncharted but early exploration suggests a height of 3,000m, less than 10,000ft, for the highest point, but at just 46 million km from the sun, the planet’s cliffs are likely to be a bit on the soft side, permanently semi-solid. Wilkins equates their consistency to that of unset concrete.

And if the heat does that to rock, think of what it would do to flesh and bones. A spacesuit capable of protecting the climber from temperatures of more than 600C would be needed.

If the space climber survives the sun’s nearest planet, it is unlikely he or she will fall in love with Venus. Described in the Rough Guide as the Solar System’s most brutal mountain, Maxwell Montes’s 11,000m (36,000ft) summit is likely to be cloaked in poisonous and corrosive sulphuric acid clouds, which will eat away all but the toughest climbing suits.

Down at ground level, these dense clouds provide a bone-crushing atmospheric pressure 93 times the Earth’s. Throw in a temperature of up to 500C, and Maxwell is definitely an alpine-style target, with a quick up and down necessary before the climber’s body succumbs. Probes that have landed on the planet have lasted only 20 minutes before packing up.

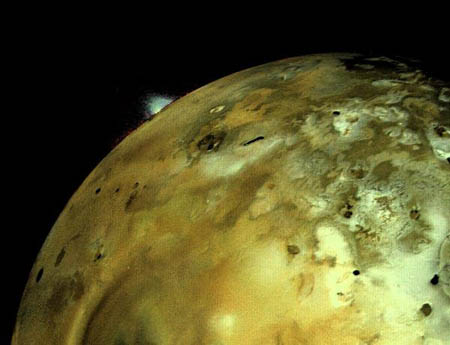

Beyond Mars, the huge outer planets have no mountains – the huge masses consisting of gases. So the would-be space climber will have to search out their satellites for mountaineering adventure. The Rough Guide recommends Io, Jupiter’s third largest moon, for the alpine space traveller.

A fairly untechnical climb of 11,000m awaits the conqueror of Boösaule Montes, Io’s highest peak. So far so good; except that, within 10 minutes, our climbers would be reaching the acceptable level of cosmic radiation. A day on Io would deliver three times the lethal human dose. Lead climbing suit, anyone?

As if the radiation levels weren’t enough to frighten the most intrepid explorer, there are countless active volcanoes on the moon, any one of which could erupt under the climber’s feet.

It’s then back into the expedition spaceship for the trip to Saturn, its shapely ice rings providing a fine photographic opportunity. Saturn’s tiny moon Mimas gets the Rough Guide five-star mountain award for one of the most unusual peaks – an underground mountain.

In the centre of the 10km deep Herschel crater lies a 6,000m (19,685ft) mountain. Fight your way through radiation almost as severe as Io’s, with a distant sun providing a paltry temperature of only –200C and you will be standing on Mimas’s tallest peak and still be below ground level.

Travelling outwards from Saturn may feel like the butt-end of the Solar System as Uranus comes into view. While the planet is a mass of noxious gases, its pleasantly named satellite Miranda provides a mountaineer’s dream: ice cliffs as high as Everest and 20km long.

The space climber is going to need some serious crampons and ice axes to contend with hard frozen cliffs in temperatures again of –200C. And a good head torch would be an idea; the sun will appear as just a bright star, 400 times feinter according to Wilkins.

The Saturn V rocket: useful for reaching those hard-to-get-to routes. Photo: NASA/courtesy of nasaimages.org

Neptune, the final port of call for the Seven Summits interplaneteer, is a bit of a damp (but cold) squib on the expedition. Triton, by far the biggest of its moons, has nothing much over 1,000m. Think Glyder Fawr, but with much less atmosphere and even colder, down to –233C, and no smiling Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Team members to get you out of trouble.

Beyond Neptune lies Pluto, ignominiously demoted from the planet league, cast off as brutally as poor old Sgurr nan Ceannaichean’s downgrading from the munro list. Little is known of this hugely distant planet, so it lies outside the scope of the Rough Guide, which is just as well, as the Seven Summits analogy would then break down.

So, the next major mountaineering quest may lie outside of the Earth’s realms and beyond most equipment manufacturers’ technical capabilities.

But, somewhere, some day, the progeny of some of today’s top mountaineers may be able to consider consulting Alasdair Wilkins Rough Guide to Solar System Mountaineering.

Me, I’ll probably stick to the Wainwrights.

Have a look at the io9 website for more details and prices (joking, of course!).

john skorupa

04 October 2010got easier ways to die

Andrew Szalay

06 October 2010For a climber on earth, the adventure of mountaineering on Mars, Io or any of the other orbiting bodies would be completely different. For instance, sending Olympus Mons in significantly reduced gravity from earth would mean being able to bound up to the summit once past its calderra. Also, the space suit would become the mountaineer's tent and shelter.

Also, did you see the video of the climber rapelling deep into the volcano? Well, it would be a little hotter on Mars too.

All mountaineering is about meeting challenges and having the drive, method and risk analysis to meet them. Scaling peaks off our beloved Earth is just a different kind of adventure.

Andrew Szalay

http://suburbanmountaineer.com/

Yanchik

11 October 2010The author unfairly downgrades Olympus Mons. Sure, the shield itself is easy, but there's a big old steep section of cliffs rising out of the planetary surface more-or-less vertically to the start of the "summit cone." Quite a challenge.

In fact, a challenge already written up: Kim Stanley Robinson's book of short stories that follow his Red/Blue/Green Mars trilogy describes a couple of British climbers en route.

Y