Ben More and the Crianlarich hills: inspiration for Naismith's Rule

Life, inevitably, has its ups and downs. And we hillwalkers love them.

It’s why we set out, week after week, to slog up another fell or mountain, panting both in anticipation of an increasingly panoramic view and at the pain of hauling our bodies and kit up the gradient. And after a sojourn spent putting names to peaks, chomping on sandwiches or even just trying to find the elusive summit cairn, it’s back down to the valley, lungs replenished, legs rejuvenated, at a rate much faster than the clomp up.

Or is it? Here’s a curious thing: that journey down the hill may not be quite as fast as you imagined.

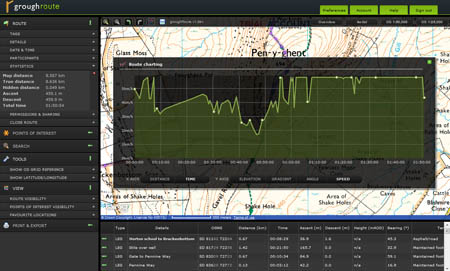

I’ll let you into a secret here. For the past several months, we at grough have been working on a major mapping and route system that will be unveiled in a few weeks. As part of the service, grough route will enable users to plan the duration their walk, depending on how steep the path is, how long, and what type of terrain will be encountered.

The online system will have lots of features, many not available on any other route systems, but fundamental to the ability to plan and walk a route is the ability to forecast how long the journey, or legs of the trip, will take.

It’s not a new concept. In 1892, William Wilson Naismith devised the rule which, for more than 100 years, has been accepted as the best way to deal with the fact that human beings can’t walk uphill as fast as they can descend slopes. Naismith was an accomplished mountaineer, one of the founders of the Scottish Mountaineering Club.

Naismith’s Rule was the result of Willie’s May walking trip among the Crianlarich hills, taking in Cruach Ardrain, Ben More and Stob Binnein. Taking calculations as he tackled the three munros, he formulated the basic speed on good terrain of 3mph on the flat, with the addition of half an hour for every 1,000ft of ascent. Metricised, this has become 5km per hour with 30 minutes for every 300m climbed, which is handy because it can be easily measured as one minute per 10m contour line crossed.

So far, so good, though Naismith made no additional calculation for descent. Over the decades, many variations, corrections and adjustments have been put forward to enable the venerable chartered accountant’s rule to be made more accurate.

grough route will enable users to plot their speed and use OS mapping

The most tortuous and probably the least commonly used are Tranter’s Corrections. For these, we have to be grateful to another Scottish mountaineer, Phillip Tranter. His table relies on working out your individual fitness and applying this to Naismith’s Rule to find out how long an ascent should take you. Tranter was himself quite a fit chap – he has a Glen Nevis circuit named after him and was the first man to do two rounds of the munros. According to Tranter, the time taken to rise 300m in a 800m linear walk puts you on the fitness scale between 50 – very unfit and 15 – which should see you chopping Naismith’s time in half.

Tranter’s Corrections also have further variations: walking with a headwind, a 20kg load and at night all mean coming down a fitness level, and terrain type can mean either one or two levels down on the scale. We could add that Smith’s variation on Tranter’s Corrections to Naismith’s Rule state that the number of units of alcohol consumed the previous evening is proportional to the level of nausea and cerebral pain experienced trying to achieve Tranter’s level 15.

Few but the most obsessively quantitative have more than a stab at an accurate rating on the Tranter scale. It helps, of course, if you have a handy 800m long 1,000ft hill outside your back door.

None of these really address any adjustment for coming downhill. Commonsense would suggest that it is going to be quicker descending than ascending. It’s important to be able to predict as accurately as possible when you are going to arrive at a certain point, particularly when conditions are less than ideal. Naismith is still at the heart of mountain training when candidates are taught to navigate for qualifications such as the mountain leader or walking group leader awards.

The ‘bible’ of mountain training was the late Eric Langmuir’s Mountaincraft and Leadership. Langmuir admits that descents provide a conundrum.

“Going downhill poses a bit of a problem,” he said. “Most walkers naturally increase their speed going down fairly gentle slopes of between about 5 degrees and 12 degrees. There comes a point, however, at which the time taken is more than would be taken walking the same distance on the level because of the extra care that is required.

“Over a day’s journey, it is normal practice to discount descent, on the assumption that increased speeds on the gentle descents will be compensated by slower speeds on the steep ones.”

He concludes that, for short distances, the following formula should be used: for gentle slopes downhill, reduce time by 10 minutes for every 300m of descent; for steeper slopes, add 10 minutes for every 300m you go down.

I’m not sure this calculation bears scrutiny. When we set about determining the default adjustments for the timing of legs on grough route, we encountered a problem here, of which more in a moment.

Hillwalking by Steve Long is ‘the official handbook of the Mountain Leader and Walking Group Leader schemes’. Long sticks with the generally held adjustment for downhill walking: “Although downhill sections can be ignored over greater distances, timing can be affected on individual sections,” Hillwalking says. “On gentle slopes, the effect of gravity allows slightly faster progress than on flat ground. As a rule-of-thumb, one minute for every 30m of descent can be subtracted from any timing calculations. Conversely, steep descents may require this amount to be added to the total time.”

Let’s take a close look at this: let’ say you descend a hill, walking for 1km down a slope at the steep end of the proposed adjustment, 12 degrees. Walking at 5km/hour, you would normally expect to cover the ground in 12 minutes.

However, a slope of 12 degrees over this distance will drop you 213m. Using the 10 mins per 300m descent formula, we should knock about seven minutes off our time, so the leg should take us about five minutes. In doing so, we would have covered the ground at 12km/hour.

Fellrunners are probably the only people who come down Pen-y-ghent at 12km/hour

Now, I don’t know about you, but I reckon 12km/hour is way beyond most walkers’ capabilities. In fact, the only people who regularly descend a hill at that rate are fellrunners and those unfortunate enough to have gone into a barrel-roll after stumbling on the way down.

grough’s programmer drew this anomaly to my attention, so I decided to conduct a very limited, and unscientific experiment: I walked up and down Pen-y-ghent, the diminutive but shapely fell overlooking Horton in Ribblesdale in the Yorkshire Dales.

I don’t pretend to be super fit, and could certainly do with losing a few pounds to help me get up the hill. I reckon my average walking speed is about 5.5km/hour, so it was interesting to analyse the results.

Up the long slog from Brackenbottom to the Pennine Way, my speed was round the 4km/hour mark, slowing to just 2k on the steep section on the hill’s southern escarpment. No great surprises there.

But coming downhill, whereas I might have expected to get up a good head of steam, I actually found I was as slow as some of the uphill legs, managing only 4km/hour at first. Only when the route really started to flatten out, with an angle of 5 or 6 degrees, did my pace approach 6km/hour.

So maybe it’s time to look again at the concept of taking away time for many hill descents. While admitting that the above experience was just one day’s short walk, the results were quite surprising to me.

grough route will enable you to put in your personal estimates for all kinds of terrain and slope: we want it to be as accurate and as useful to walkers and other outdoor users as possible, but we think we may have to rethink our default values. After many unquestioning years of accepting the received wisdom of timing on hills, perhaps we should now start examining our downhill speed.

Willie Naismith, of course, left the subject of descents out of his original rule, and it was only subsequent adjustments to this that have introduced what may by a fundamentally incorrect variation. Perhaps the Victorian mountaineer was right.

However, we will need to set a default value for our route planning and mapping system. So what are your experiences? We’d like to know. Do you hit the throttle coming downhill, or do you, like us, probably take smaller steps to improve your braking, and take a bit more care not to let gravity overtake you?

You can use the comment box below to let us know, and share you knowledge with other grough readers who may be wondering why that five-hour walk inevitably seems to take an hour longer.

eBothy Blog » Naismith’s Rule and a new online route planning app

13 July 2009[...] have an interesting article about Naismith’s Rule and associated gubbins by various baggers who have modified it over the [...]

john hee

13 July 2009Defintely faster downhill, than up (!) but short steps

I work on on average of 2 mph on the fells, reducing to 0.5 mph for extended uphill stretchs of > 1hr

Average seems to work at around 2mph over a 5-8 hr day whatever the terrain

In comparison long trips on Datrmoor up the daily average to around 2.6-2.8 mph

Veryinterested in what the new app comes up with

Dave Hewitt

14 July 2009Interesting piece. I've never really been one for crosschecking my own hill pace against Naismith or his modifiers, but I have long had an interest in keeping an eye on my own speed (or otherwise) on the hill. In recent years I've got into the habit of noting down timings at summits, cols and other significant points on pretty much every hill day, partly as a carry-over from a spell as a runner (not very good and not sustained for long before injuries saw me off), partly as an inheritance from my late father, who always seemed to be noting down times, prices and so on using scraps of paper and tiny, near-indecipherable script.

I'm an inveterate repeater of hills, so knowing how long a particular stretch took me on a previous visit can have practical benefits both in terms of not getting benighted (or missing my tea) on some future occasion and also monitoring how well I'm doing, fitness/health-wise. I know other people who do this too, and it allows them to develop a sort of bespoke Naismith Rule. Everyone is different, and while general assessments such as Naismith are undoubtedly useful, there's even more mileage (pardon the pun) in knowing one's own very personalised rate of progress over different types of ground. In my own case, being very tall (over two metres) is undoubtedly a factor. It means I'm relatively faster going uphill or on the flat (or what passes for the flat in hill country) than I am going downhill. Have you ever seen a giraffe trying to lope downhill?

Two other thoughts. One is that terrain is a massive factor in speed-over-the-ground. I do a lot of my hillgoing in the Ochils, on lovely grassy paths, so I need to bear this in mind if attempting to predict timings for a trip into Fisherfield. Similarly, family connections see me in the Lakes half-a-dozen times a year, and hill outings there always seem a few percent quicker than for the same effort-expenditure in the Highlands - because the Lakes fells with their numerous paths and their Herdwick-nibbed grass are, on the whole, less rough than various hills further north. (In Galloway one gets both on the same outing: a mix of forest tracks, where one marches along at a faster-than-Naismith rate, and mega-rough stuff where progress can be bushwhack-slow, particularly in summer when the vegetation is up and the insects are out.)

Also, I've long felt that time-on-one's-feet is a big factor in assessing tiredness, every bit as important as the standard factors of distance and ascent on which all these formulae tend to be based. One example: last year I had a grand day going round all seven of the Crianlarich Munros from the road-end at Inverlochlarig. I didn't work out the ascent or the distance (or, if I did at the time, I've forgotten now); but looking at my notes I see it took me just under 11 hours, of which around 50 minutes was spent sitting around. It was a big day - satisfyingly so - but had I gone a bit slower, taking 12 or even 13 hours over it, I would almost certainly have finished feeling more tired, because I'd have been on my feet for longer and would have been less in synch with my natural pace and rhythm on the hills. Something similar probably applies to everyone, whatever one’s speed and strength.

Andrew Baxter

15 July 2009From my own walking experience I have always assumed that it can take me as long to descend a steep route as it took me to ascend. This is particularly true if I am off path or on slippery ground in wet weather. My knees find it difficult coming down hill so there is always a natural tendency to walk slower.

Comparing GPS tracks of my hill routes with the estimated journey time when converted to a route in Memorymap suggests that adding 1 minute for every 10m of descent seems to be fairly accurate. As I am a plodding walker I assume that it takes me 1.5 minutes for every 10m climbed.

Jim Cassidy

18 July 2009I'd concur with Andrew, some descents can take a similar time to the ascent, it depends on terrain, weather, tiredness and visibility.

Bob Feuillade

20 July 2009I think that Naismith is a very misunderstood chap. His whole idea was to have a method to estimate the time for a DAYS walk, not short bits of it. It is not a method that will be acurate for short sections and was never ment to be.

Every time you take another step you change speed. We continually accelerate and decelerate as our feet pass over the ground. There are so many variables, the surface, length of vegitation, solidity let alone if the individual step is higher or lower than the one before or after. and all this is independant of the general slope direction, up or down.

If you put a gps track into memory map, or the like. Blow up the map to maximum scale and follow the track with your mouse. You will see that your speed varies so much that an acurate estimate over short distance is impossible. Naismith , sensibly, didn\'t try! He worked out that over the whole day, his estimate would be about right. That was all he needed. That is all I need to be sure that I\'m not benighted.

Sometimes I may be a bit early home, somtimes a bit late but I don\'t care too much as long as I can have an adventure without having too big an epic! I think you can get a bit too involved with trying to analise these things somtimes, so involved that you actually forget what you were doing the exercise for in the first place. To have a nice day out in the hills!

BILL PATTISON MBE

22 July 2009I would agree with John Haw,In over 60 years of hill bashing Ive found that 2 miles per hour in mountainous country works out pretty well over the day.I go on the hills for enjoyment not a mathematical workout,Get a life.

Steve Long

21 August 2009As the author of "Hillwalking" I'll be interested in your results. Like some of your comment contributors I don't like getting bogged down in maths. For navigating on individual legs, counting paces is much more useful than timing. For planning a day or half day, Naismith balances out reasonably well with the rough and ready modifications you've quoted from my text and Langmuir's.

For individual legs your tests show that there is potential for a more subtle distinction to be drawn, since the 12 degree example clearly doesn't work. I have to admit that I spent a lot more time thinking about uphill than downhill in the text (my favourite is the 1.5 minutes per contour for steady uphill walks - ignoring the horizontal measurement). Maybe a simple variant might be constructed around 0.5 minutes per contour for medium slopes on the same basis. For your example of 213 metre descent, this would come to 11 minutes, but it wouldn't work for the 6 degree slope which would have half as many contours.

I would say that the 12 degree slope is not a gentle slope as intended in the quoted text. A 6 degree slope is much more like it, and as you pointed out in the article, your speed approached 6k/hour on a 6 degree slope.

I will watch this forum with interest though. Hillwalking will need reviewing in the medium term, and if you come up with something better I will be keen to incorporate your findings.

Dariusz Kowalczyk

21 March 2013> we would have covered the ground at 12km/hour

Exactly. However if we assume 4 km / h, final velocity at -12 degrees would be 9.48 km / h.

Which speed takes Langmiur in his book - 4 km / h or 5 km / h ? Some of publications say, that 4 km / h.

But we would have still two thresholds - at 5 degrees (from 4 or 5 km / h to 6.2 km / h) and at 12 degrees (from 9.48 km / h to 3.4 km / h).

Dariusz Kowalczyk

22 March 2013Correction !!!

Assuming basal sped as 4 km / h we obtain:

4 km / h (or 5 for 5 km / h) between 0 and -5 deg,

4.97-7.58 km / h from -5 to -12deg and

2.72 km / h and less below -12 deg

Southern California Hiker

05 May 2017"Few but the most obsessively quantitative have more than a stab at an accurate rating on the Tranter scale. It helps, of course, if you have a handy 800m long 1,000ft hill outside your back door."

That's the crux of the issue. I can't find a trail which meets that standard. By my calculations, it's a 37.5% grade, or about 20%.

Though I live in an area with many steep mountains, I can only find short sections of trail that approach the necessary steepness. There are some cross-country routes, but those have obstacles like brush, rock, or loose material that would affect the result. There are a number of long outdoor stairways in my neighborhood, but not that are long enough. There's 1000' building downtown, if they'd let me climb their stairs. Most people, including Tranter, don't have easy access to such tall buildings.

Does anyone know where Tranter lived or hiked specifically? I'm beginning to wonder who, if anyone, has been able to perform the test that Tranter used as the basis for his corrections.

It seems like it'd be possible to come up with a more practical test that could be used to fit people into the same fitness levels.

Naismith’s Rule and D – Walking Everywhere in Oxford

13 December 2022[...] the promise of “for fitness and fatigue”, and a quick perusal of internet search results agrees. Let’s quickly see what it says about the same example walk as [...]