Buachaille Etive Mòr: everyone's idea of a mountain

Hands up all those who knew there was an official definition of a mountain.

No? Neither did we, until we delved a little after hearing of the determined efforts of three hillwalking enthusiasts to elevate a Welsh hill to the pantheon of British mountains. It’s official! screamed the headlines of the mainstream press as they whooped over the fact there was a vague similarity between the walkers’ efforts and the plot of a 1995 film starring a foppish Englishman.

The three, Myrddyn Phillips, John Barnard and Graham Jackson had their eye on two potential candidates for the title of New Mountain: Craig Fach and Mynydd Graig Goch, both in north Wales and tantalisingly close to each other. Both were marked on Ordnance Survey maps as being 609m high, which converts in old money to 1,998 ft – 60cm short of the magic mark.

Mynydd Graig Goch

Apologies now for the necessary mixing of the two systems. All measurements on OS maps are now – and have been for some time – SI units: metres, km etc. But, and here’s the interesting point, The OS accepts that a ‘mountain’ is 2,000ft or higher.

I spoke to Paula Good of the OS. She said: “We just go with what is generally regarded as being one: 2,000ft.” And then, rather deflatingly, Ms Good told us: “The actual height of a mountain is not that important to us.” The OS, the Government-owned ‘trading fund’ responsible for the nation’s mapping, concentrates its efforts on things which are more useful to the emergency services and utility companies, such as new roads and housing.

After consultation with a colleague, Ms Good also confirmed that, alarmingly for peak baggers everywhere, the spot heights of hills on the OS’s paper maps are only accurate to plus or minus 3m.

Even Myrddyn Phillips, one of the men whose efforts led to the mountain total being raised by one, admitted that the 2,000ft figure was an arbitrary one. He told grough: “It is purely subjective. But there is a rich and long history of listings in Wales of 2,000ft hills. The majority of lists that have been produced are based on that figure.”

This view is echoed in the official statement the amateur surveyors issued: “The first list of 2,000ft mountains in England or Wales was published in 1925 by Carr and Lister and many authors have followed since.”

And there was a precedent: “In 2006 we found, following a comprehensive survey, that Birks Fell in the Yorkshire Dales exceeded the magic height. This was achieved using a Leica automatic level to survey to the summit from a trig point 2km to the South. The result was subsequently confirmed by the Ordnance Survey.

The surveying party on Craig Fach, with an unashamed plug for Leica Geosystems. Photo: John Nuttall

“Currently used lists,” said the trio, “Are those of John and Anne Nuttall – the nuttalls – and of Alan Dawson – the hewitts,” of which more later.

So, with the clear intention of adding two more mountains to the 188 ‘official’ Welsh ones, the men set off on a typically horrible summer day on 11 August, accompanied by James Whitworth, an expert at Leica Geosystems, which makes surveying equipment.

The goal was to cart a Leica SmartRover to the top of the two hills and get accurate readings from the satellites of the American GPS network. SmartRover sounds like an intelligent search dog, but it’s actually a gizmo on a stick, with an antenna for picking up the weak signals and then comparing these with ground-based correction data which means you end up with an accuracy of a few centimetres, even on a wind- and rain-swept Welsh hill.

Disappointingly, it soon became evident that Craig Fach was going to fail the test. Although the OS insisted on two hours’ worth of data for verification, within minutes of setting up the gear, it was clear that the hill would remain just that – a high hill, 608.75m tall – 1,997ft 2½ inches.

Mr Phillips explained: “On the first hill, we knew within minutes that it would not come within the measurement.

“That also helped us because we wanted to do two hills in one day. That enabled us to cut our day short and move on to the next hill.”

So, it was back down to Pen-y-pass and into the cars for the 45-minute trip to the western end of the Nantlle ridge above the village of Nebo for a crack at the second hill, Mynydd Graig Goch. The craggy summit of the hill has a pinnacle of rock, to which the measuring device was attached. For more than two hours, the readings were taken: 7,000 in all and, just like in that film, the team came down a mountain. The Mynydd measured 609.75m – 2,000ft 6 inches – bingo!

Incidentally, despite living in Welshpool, the location for The Englishman Who Went up a Hill But Came Down a Mountain, Mr Phillips said the idea never occurred to them that they were somehow re-enacting the plot. It was, he said, pure invention on the media’s part.

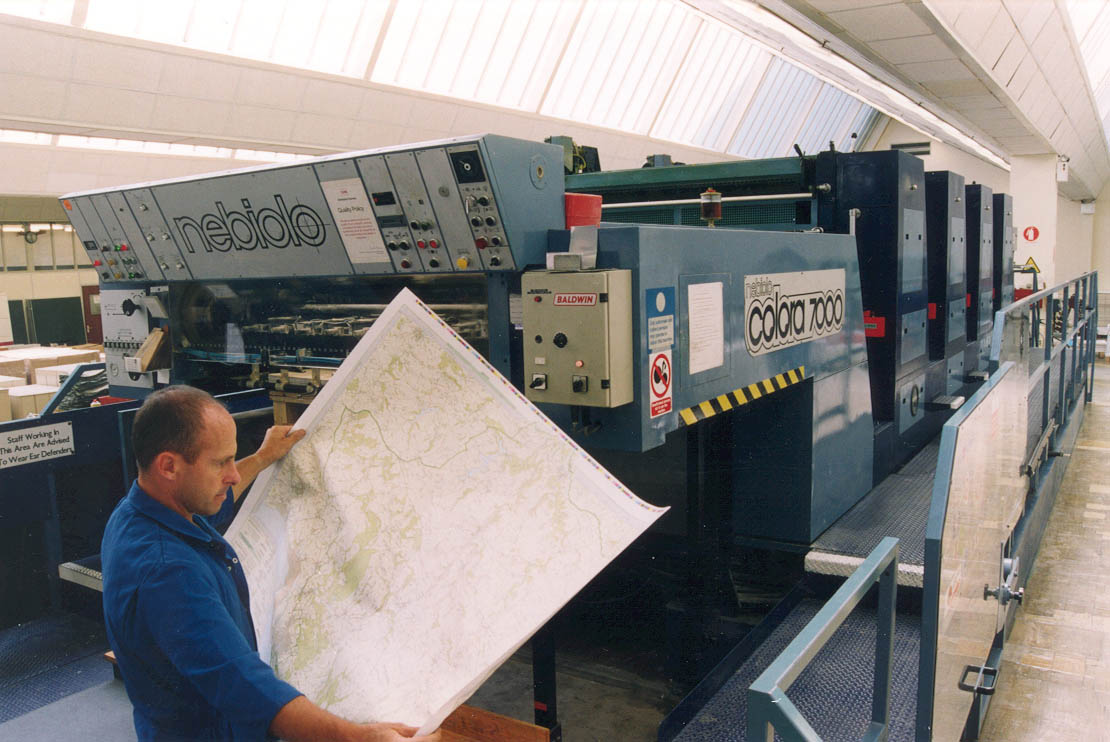

Printing the OS's maps

Paula Good praised the amateur surveyors’ efforts. She said: “It was good for the walkers to go out and do what they did. This is the first time it has happened where it was measured and it was found to be a mountain.”

The OS database has already been updated, but it will take a little longer for the paper versions to be amended. They are revised on a five-year cycle.

So, where does this leave the lover of mountains? Certainly, collectors of hewitts and nuttalls now have a new one to bag, but the list of mountains in Britain is mind-bogglingly complicated.

The best known, of course, are the munros, named after Sir Hugh Munro who listed them in 1891. The munros are Scottish mountains over 3,000ft (914.4m). There was an attempt to add to this list last year, but the two candidates, Beinn Dearg and Foinaven didn’t live up to close scrutiny and the number of munros remains 284. But it’s not that simple. The Scottish Mountaineering Club, guardian of the right to determine what is and isn’t a munro, dictates that there should be a drop of at least 500ft (152.4m) between the summit and neighbouring mountains to qualify. Otherwise, it’s a ‘munro top’. There are 227 of them. Just when you thought you were starting to get your head around the concept, up pops the murdo. The 444 murdos are over 3,000ft and have a prominence of at least 30m (98ft) – oh how we love to mix our imperial and metric systems.

Ben Nevis, undisputed king of the munros

Now pay attention, we’ll be testing you later.

Let’s work our way down a little. A gentleman called John Rooke Corbett decided in the 1920s to catalogue the munros’ smaller cousins, those which measured up at between 2,500ft and 2,999ft –well, I suppose technically 2,999 ft 11½ins – but these too had to have a relative height, a prominence, of at least 500ft. And so were born, listwise at least, the corbetts: 219 of them, spread across Scotland, from Harris to the Southern Uplands.

Next in the league table of high ground come the donalds. Once again, named after the compiler of their details, Percy Donald. Here, the ground starts to get decidedly shaky. A Scottish hill with a height of at least 2,000ft and a relative height of 30m automatically gains the status; however, if the hill is of venerable topographic merit and has a relative height of only 15m, it will be held to be a donald. Subjectivity rules in donalds’ world. At present, there are 89 of them. If the wind changes direction that number may change.

In a similar vein, grahams, compiled by Alan Dawson but named after Fiona Torbet (née Graham) are between 2,000ft and 2,499ft, with a relative height of at least 150m. Their original classification was Elsies (LCs – Lesser Corbetts – geddit?). My brain is beginning to hurt.

Ingleborough, Yorkshire's cousin to Table Mountain

Whether most Scottish hillwalkers would consider them mountains, as they would be south of the Border, is definitely a moot point. Does Scotland have different mountain criteria to the rest of Britain?

Marilyns, coined uproariously as companions to munros, are based purely on relative height and crop up all over the place: Scotland, Wales, England, even the Isle of Man. One, Black Mountain, straddles the Wales-England border, so is even more subject to argument.

There are 1,554 marilyns in the British Isles, so baggers have a major task, though munro ‘compleatists’ will have summited many of them. They have one single criterion: a drop of at least 150m. Ireland has a further 453 of them. Many of these, of course would satisfy no-one’s idea of a mountain. Cliffe Hill, in Sussex, for instance, is a 164m grassy lump the summit of which is desecrated by a golf green, complete with flag.

Let’s cross south of the border, where we will encounter the aforementioned nuttalls, hewitts, and some very esoteric and subjective ‘mountains’.

The hewitts – Hills in England and Wales and Ireland over Two Thousand feet – are, well exactly that. Except, according to their official keeper Alan Dawson, they too have a relativity factor: at least 30m drop around them. This addresses one of the major criticisms of nuttalls, which are hills in England and Wales over 2,000 ft but with a prominence of only 15m. This puts Pillar Rock, on the Ennerdale fell Pillar, into the list, which creates problems for walkers because the ascent of Pillar Rock is a graded climb by whichever route taken.

Nuttalls now number 442 and Hewitts 526, of which 211 are in Ireland.

The Old Man of Coniston, formerly Lancashire's highest peak

Venturing into further controversy, there exist county tops. Mr Corbett was an early chronicler of the highest ground of each county. However, since then there have been major revisions of the county boundaries. In this respect, pity poor old Lancashire, whose high point used the be the imposing Old Man of Coniston, 803m (2,635ft) high and, to all but the most ardent deniers, a mountain. Lancashire’s high point is now the nondescript grassy lump Green Hill, which pips nearby Gragareth by a metre and which most people would tramp over unknowing on their way to Great Coum, donated to the fledgling Cumbria in 1974.

And how about Scotland and Wales, where the situation is, if anything, even more confused, with historic counties mingling with new regions and unitary authorities. So the highest hill in Dumfriesshire is the 821m White Coomb, yet the high point of Dumfries and Galloway is Merrick, at 843m.

Losing the will to live? I’m not surprised.

White Coomb, Dumfriesshire's top peak

There is no doubt, however, that the wooden spoon for the old counties goes to Lincolnshire, with a top height of a mere 8m – that’s 25ft above sea level – at Pinchbeck Marsh. Show me a man who would hold that to be a mountain and I’ll show you someone who needs to take more water in his drink.

Which brings us back to the vexed question of what makes a mountain and the even more difficult subject of subjectivity. The king of lists by subjectivity is the wainwrights, whose inclusion in the list relies on the fact that they were described in a series of books.

Admittedly, the books were written by the most renowned chronicler of the Lakeland fells since Coleridge, but subjective they are.

Holme Fell, at 317m, barely scrapes into the one-thousand foot hall of fame, but still warrants a chapter in Alfred Wainwright’s fourth book in the series of Pictorial Guides. Yet Helm Crag, the diminutive Grasmere hillock with a decidedly precarious sting in the tail for those brave enough to risk the ascent to the top of its Howitzer, probably deserves the accolade of mountain more than, say, the aforementioned Green Hill, whose summiting is a triumph only of navigational expertise to find its slight rise on an otherwise homogeneous grass ridge.

Julia Bradbury

Castle Crag, which even warranted an ascent by the glamorous latter-day wainwrighter Julia Bradbury, can’t even manage a thousand feet. Yet it’s an essential for those who want to tick off all the wainwrights.

Is it worth an ascent? Well, that’s up to you. And that, I think, is the essential factor when deciding whether a hill is a mountain. In the end, whether you choose to walk up a hill and think of it as a mountain, or go only for ‘true’ mountains is a personal decision.

One thing is for sure: three men (and a surveyor) did go up a Welsh hill and came down a 2,000-footer, and Hugh Grant was nowhere to be seen.

For that, be grateful.

Jon

30 September 2008"The Scottish Mountaineering Club, guardian of the right to determine what is and isn?t a munro, dictates that there should be a drop of at least 500ft (152.4m) between the summit and neighbouring mountains to qualify. Otherwise, it?s a ?munro top?." Not so, there is no drop criterion for Munros, though the SMC appears to have been heading slowly in that direction. For example, Sgurr Mhic Choinnich (Skye) is a Munro, not just a Top, with a drop of about 56 metres.

Guest

30 September 2008[smiley=think] Your Munro definition is off kilter. It's the Corbetts with the 500ft all round rule. The Munros are much more subjective and there's no definitive criteria (at least that's my understanding of the situation

grough editor

30 September 2008We stand corrected. I did say my brain was hurting!

Brian Knowles

05 November 2008Very informative and amusing in equal measure

Phil McLean

07 November 2008Further to the above Munro-related corrections, there are currently 284 Munros, not 227 as quoted. Prior to the 1997 revisions there were 277 Munros.

grough editor

07 November 2008We don't say that there are 227 munros; we state there are 284. There are, however, 227 munro tops. I feel another headache coming on

Phil McLean

10 November 2008I do beg your pardon - my mistake!

Richard Smith

16 February 2010"the wooden spoon for the old counties goes to Lincolnshire, with a top height of a mere 8m". Err, no it isn't. The highest point of Lincolnshire is Normanby Top in the Wolds with a height of 168m. 8m is the height of the highest point of the Parts of Holland, one of the three historical subdivisions of Lincolnshire (much like the Ridings of Yorkshire). Huntingdonshire is the traditional county with the lowest highest point, the aptly named Boring Field at 80m.