Britain has 15 national trails – long-distance paths and bridleways that offer a challenge to anyone who wants to walk, cycle or ride a horse over linked rights of way.

Britain has 15 national trails – long-distance paths and bridleways that offer a challenge to anyone who wants to walk, cycle or ride a horse over linked rights of way.

Maw Wyke Hole on the Yorkshire coast

Surprisingly, the Coast to Coast Walk isn’t one of them. Or perhaps it’s not so surprising. Its creator was the original Grumpy Old Fellwalker Alfred Wainwright, best known for his Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells but who, later in his life, turned his attention beyond the Lakes and completed books on the Yorkshire Dales limestone country and a companion to the Pennine Way, the grandfather of all our National Trails.

But the Coast to Coast is Wainwright’s creation. Or rather, A Coast to Coast Walk is. Although thousands now stomp across northern England on his route, he was at pains to point out when he wrote his guide, that he was only suggesting the best route, not prescribing it. As he says in his introduction: “Some walkers may choose to vary it in places, either to make additional detours or to short-cut corners, or even follow their own course over lengthy distances. Such personal initiatives are to be encouraged.”

Now, the Wainwright Society, formed to promote and enjoy the works of the late borough treasurer, is campaigning to have the route upgraded and recognised as a National Trail. I’m not sure ‘Red’ would have approved. His main intention was to draw walkers away from overused footpaths such as the Pennine Way and into less frequented uplands between the Cumbrian coast and north Yorkshire.

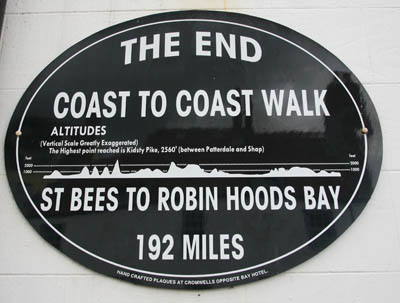

Even so, the Coast to Coast has grown in popularity to the point where thousands complete the 192-mile trek every year and whole communities pander to the footsore walkers and the economic benefits they bring. The walk has even taken second place in an international poll of long-distance routes. It has the reputation of being one of the best for variety and sheer quality of landscape. It’s certainly not the shortest route across northern England: a quick glance at a map will confirm that. It was devised by Wainwright to link three national parks, favour high ground over low land and avoid towns as much as possible.

There is a multitude of approaches to tackling the route. Many arrange for their gear to be transported by van from one night-stop to the next, which means they travel light, with a day pack. Others backpack the whole route, camping and carrying all they need, or as near as possible. There are many places to stay, from bed-and-breakfasts to youth hostels or even hotels if the budget runs that far.

Two things are certain though: the walk starts at St Bees in Cumbria and ends at Robin Hood’s Bay on the Yorkshire coast; or vice versa. 14 days seems to be a typical period for the crossing though, again, you can put a sprint on or take your time. There are no rules.

Two things are certain though: the walk starts at St Bees in Cumbria and ends at Robin Hood’s Bay on the Yorkshire coast; or vice versa. 14 days seems to be a typical period for the crossing though, again, you can put a sprint on or take your time. There are no rules.

Convinced by the plaudits lavished on Wainwright’s route, I dug out my boots and loaded up my pack. Now, maths was never my best subject at school so, to keep things arithmetically simple, I set a ten-day period as my goal. Even I could work out that makes for about 19 miles a day. Not easy, but achievable, I thought.

Then I tried on the pack. I’m used to going as lightweight as I can on my day excursions to the fells, so it was something of a shock to find 18kg bearing down on your shoulders and hips and my thoughts turned immediately to the effort of getting me and the rucksack over Greenup Edge and Grisedale Hause. The knees buckled even standing still!

So, for the record, here’s what was in the big bag: a tent, sleeping bag, Therm-a-Rest, water in a two-litre bladder, stove, pans, gas canister, mug, knife and fork, two pairs of trousers, one pair of shorts, a spare lightweight base layer, three pairs of trolleys, three pairs of socks, two tee-shirts, two microfleeces, a waterproof jacket, waterproof trousers, food for three days, mobile phone, wind-up charger, head-torch, two compasses, a lighter, wash kit, tea-towel, lightweight towel, GPS, notebook, Wainwright’s book plus one other guide book, pen, Dictaphone, camera and two lenses, first-aid kit, alcohol hand-wash, water purification tablets, a trowel, toilet roll, spare boot laces which were to double as a washing line, cash.

Yes, it just fit in a 50-litre rucksack, with some very careful packing. Did I use everything I took? Not quite. I didn’t use the water tablets, so I could have save myself 10g or so, and I could have got away with only one pan rather than two. And my base layer was never used, so all in all, I could have probably ditched about 300g – not enough to be significant.

I chose to walk in leather boots, not knowing what the weather would be like over ten days, although I knew this would exact a toll on the legs and feet. If I’d had space, I might have considered packing my fell-running shoes. But I hadn’t, so I didn’t.

The plan was to camp as much as possible, including wild camping where this proved practicable. I wanted to keep cost to a minimum and sleep under canvas wherever I could. I broke the route down into 30 ten-kilometre sections, plus a little 8km addition which made up the full distance. This, I figured would help me keep track of my progress, give me a mental goal and help me plan my stops.

The major gain in carrying your accommodation on your back is the flexibility it gives in choosing where to stop for the night. Of course, you can’t just throw your tent up anywhere, but if the worst came to the worst and I found night drawing in, I anticipated just searching out somewhere to pitch it and making an early break in the morning. The disadvantage, of course, is the effect of having all that weight which both puts greater strain on the body and also makes the walker less nimble over difficult terrain. Striding Edge, I decided, was not for this trip.

On the other hand, those who choose to stay in B&Bs, hostels or guest houses need to do quite a lot of preplanning. Unless you intend tackling the Coast to Coast in winter or one of the months when its popularity has waned, you’ll have to make sure you book your night stays well in advance. Because most Coast to Coasters set off from either St Bees or Robin Hood’s Bay at the weekend, they tend to arrive at villages en route on the same day and even at the same time of the day. It’s obvious when you think about it. They’ll probably set off within an hour of one another and walk at a pace not vastly different to each other, so it’s quite usual to find a particular village has a Coast to Coast ‘rush hour’. I was told by the woman in the Co-op in Shap: “We don’t normally get Coast-to-Coast walkers at this time of day.”

You can, of course, get round the problem by setting off on, say, Tuesday or Thursday. Or backpacking it and putting in long days. Or that’s how I viewed it at the time.

You can, of course, get round the problem by setting off on, say, Tuesday or Thursday. Or backpacking it and putting in long days. Or that’s how I viewed it at the time.

The Coast-to-Coast path on Glaisdale Moor

Research does pay off. There are walkers’ forums which give useful hints and opinions and there are surprising places to stay. One pub on the route allow you to pitch your tent on its beer garden – particularly handy at the end of the day when a bit of liquid nourishment may be called for.

Be aware, too, of the latest developments. The YHA has a programme of closures of some of its less profitable hostels, which affects some on the Coast to Coast route. Keld, for instance, no longer has a youth hostel; it’s now a restaurant. On the other hand, Kirby Stephen’s has now reopened as an independent hostel.

So the decision was made: backpacking, camping, West to East, 19 miles (about 31km) a day.

For the first two days only, I pre-arranged where I was going to stay, so at least I had that part sorted before I set off. The rest would be done on the hoof. Stonehouse Farm is right in the middle of St Bees, within a few yards of the railway station. It caters for B&B walkers but, more importantly for me, allows camping on its back lawn, among the fallen clothes pegs! £3.50 got me a pitch for the night and for a bit extra you can book a breakfast.

By the way, if you are travelling by train, try breaking your journey into sections: I got the quote for a ticket halved on the National Rail website by getting prices for separate parts of the journey. Ah, for the good old, bad old days of British Rail! In the end, my journey was by car, my reliable chauffeur getting me to the West Cumbrian town as the August clouds lowered and a heavy drizzle enveloped the coast.

Perhaps it was the grey skies, but St Bees struck me as a town with a lot of history but whose best days are behind it. There’s a public school founded in 1583 by the then Archbishop of Canterbury Edmund Grindal as a free school but now charging up to £7,000 per term. The Priory Church has its origins in Norman times. The economic benefits of the nearby quarrying and mining have all but gone as have many of the tourists originally brought to the area with the coming of the railway. Many of its inhabitants now work either at Sellafield nuclear plant or at the Kells chemical works.

The Queen’s Hotel was closed ‘due to circumstances beyond control’ and the headland which would be the start of the route the following day had disappeared into cloud. Still, the Manor House Hotel bar served good food and beer which cheered me as I read about the route for the first day’s walking.

There is a grocery store in the town – during the walk it becomes very important to know where food can be bought! – and part of the station is a bistro-type bar but apart from that, there’s not a lot of exploring to be done in St Bees.

There is a grocery store in the town – during the walk it becomes very important to know where food can be bought! – and part of the station is a bistro-type bar but apart from that, there’s not a lot of exploring to be done in St Bees.

The toilet block at St Bees, complete with a row of planted toilet pans

However, compared with many places en route, it felt like a down-to-earth place and it smelt very fragrant with its masses of flowers filling the air with their perfume in anticipation of the Britain in Bloom judges. Even the public loos had a row of toilet bowls outside filled with blooms.

Camping puts you in touch with nature, and when nature decides to pour the contents of the heavens on to you, you hear every beat on the canvas. My night at Stonehouse was accompanied throughout by the rhythm section of a marching band, so it was no surprise to wake up to more leaden skies and a soaking wet tent to stuff into the rucksack. Ten days of this to come? Oh great!

St Bees to Ennerdale

The seafront at St Bees, about a kilometre from the main town, is built in the school of Sixties Bad Taste, as is so much of our seaside. It seemed an incongruous place to start the walk that encompasses the glories of northern England’s finest landscapes. At 7.30 in the morning, the only other souls about were a couple of dog-walkers, no doubt wondering who the lunatic was who was paddling in his boots.

I should explain: Wainwright’s instructions to Coast-to-Coasters are to dip the boots in the sea at each end. Actually, I’m sure the citizens of St Bees are used to all sorts of sights as apprehensive would-be traversers of the country start their venture.

There’s also a suggestion of picking up a pebble from the shore and carrying it all the way to deposit in the North Sea. I rejected this idea on two grounds: weight – I couldn’t possibly cope with an extra 5g; and, more importantly, ecological – imagine the confusion among the archaeologists and geologists of centuries to come when trying to explain how so much Cumbrian rock ended up in North Yorkshire.

As Mr Wainwright pointed out, his route starts the trek to the east coast in a decidedly westerly direction, as the caravans and bingo halls of St Bees are left behind to mount the steep slope of the South Head.

As Mr Wainwright pointed out, his route starts the trek to the east coast in a decidedly westerly direction, as the caravans and bingo halls of St Bees are left behind to mount the steep slope of the South Head.

St Bees from South Head

The route keeps company with the Irish Sea for as long as possible and the seaward view holds the attention, with glimpses of the Isle of Man, mist and cloud permitting. Pressing northwards, the Galloway hills come into sight as do, unfortunately, Whitehaven and Workington. It’s not until you finally turn towards Sandwith that you say farewell to the Irish Sea.

There was a wealth of bird-life on the cliffs, as witnessed by the large guano deposits and cormorants were a constant companion during the pleasant walk along the cliff tops. A more fleeting companion came in the shape of a dog walker met within minutes of setting off.

“You doing the Coast to Coast?” he asked. Chest swelling, I replied I was. “When you get beyond Reeth, there’s a little place called Marrick. Call in at Elaine’s tea room and tell them I recommended it. I’m the postman in the area.” I made a mental note. How many more recommendations would I receive en route?

The Lakeland fells might have been visible on the approach to Sandwith, were it not for the low cloud and drizzle obscuring everything above about 200m. Sandwith has a certain charm, with plenty of original sandstone buildings. Make the most of it, for most of the little towns and villages in west Cumbria have little to commend, certainly architecturally, being utilitarian and a little grey. Certainly, neither Moor Row nor Cleator has much charm, though Moor Row does now boast a Coast-to-Coast sculpture at the junction of the busy A595.

The Lakeland fells might have been visible on the approach to Sandwith, were it not for the low cloud and drizzle obscuring everything above about 200m. Sandwith has a certain charm, with plenty of original sandstone buildings. Make the most of it, for most of the little towns and villages in west Cumbria have little to commend, certainly architecturally, being utilitarian and a little grey. Certainly, neither Moor Row nor Cleator has much charm, though Moor Row does now boast a Coast-to-Coast sculpture at the junction of the busy A595.

In fact, to say that the route isn’t a national trail, there’s a lot of signing for it and I got the impression that these small places gain a certain pride in the small amount of fame the Coast-to-Coast walk affords them.

Dent fell lay ahead and with it the steepest climb since South Head. It’s forest track followed by a relentless slog up moorland to two peaks linked by a wet and boggy dip. Then you plunge back into forest, with a view up Uldale before following the babbling Nannycatch Beck.

The descent down the road to Ennerdale Bridge was eased by following a separated path parallel to the asphalt. The cultured, tame pastureland of west Cumbria changes here abruptly as the fells start their rise towards Pillar and Red Pike.

By now, the footpath along the south shore of Ennerdale Water was becoming a drag and seemed interminable which is a great shame because, had I been less tired, I’m sure it would have been splendid. Ennerdale is a great valley but by the end of the day, after ten hours’ walking, I just couldn’t be bothered.

Low Gillerthwaite was reached eventually, my first night’s stop. It’s a field-studies centre run by a charity that offered camping in a nice, flat field for £3.50 to the accompaniment of a diesel generator and courting geese. There are showers, washing-up sinks and toilets in the best Scout-hut style. The centre also has a welcome payphone: in these parts you’ve as much chance of getting a mobile phone signal as you have of chancing across a Wainwright comedy cabaret.

Low Gillerthwaite’s great attraction, though, is its setting. Red Pike and Pillar stand sentry to the broad valley of Ennerdale and fill the view east. But that was for another day. The generator fell silent and my head hit my improvised pillow.

Sunshine illuminated my tent as dawn’s rays penetrated the fells of Ennerdale and my spirits were lifted by the thought that perhaps the rain had departed, though there’s always the nagging doubt about weather in the Lakes, each valley having its own microclimate and there were still wisps of cumulus swirling around the tops.

Sunshine illuminated my tent as dawn’s rays penetrated the fells of Ennerdale and my spirits were lifted by the thought that perhaps the rain had departed, though there’s always the nagging doubt about weather in the Lakes, each valley having its own microclimate and there were still wisps of cumulus swirling around the tops.

By the end of the day, I was to realise that my hope of maintaining 30km a day was overoptimistic. Even more optimistic the thought I might be able to extend the distance even further and clear Grasmere. The route from Ennerdale to Easedale is tough, with more than 1,450m of ascent and it would be 6.30pm before I would gaze down towards Grasmere.

Ennerdale to Far Easedale

The continuation of the journey up Ennerdale is dominated by the ever-present Pillar and the rock from which the fell takes its name. The valley has a very Scottish feel to it, with its pine plantations and towering crags. The forest track, though easy to navigate, is hard and unrelenting for feet still recovering from the first day’s long trog.

There’s no doubting the feeling that you’ve firmly entered mountain terrain, with Great Gable guarding the head of the dale and Red Pike’s and High Stile’s steep slopes plunging to the valley bottom.

Many have remarked on the romantic setting of Black Sail youth hostel, situated at the very end of the long dale, just as the ground starts to rise to Windy Gap or, in my case, to the ravine of Loft Beck. I’ll bet it doesn’t feel so romantic when the rain stair-rods down or there’s a force-nine westerly pounding the former shepherd’s dwelling.

Many have remarked on the romantic setting of Black Sail youth hostel, situated at the very end of the long dale, just as the ground starts to rise to Windy Gap or, in my case, to the ravine of Loft Beck. I’ll bet it doesn’t feel so romantic when the rain stair-rods down or there’s a force-nine westerly pounding the former shepherd’s dwelling.

The steep clamber up Loft Beck pays off, with eventual fabulous views if, as on my visit, the clouds have lifted, right down Ennerdale to the coast from which the route starts. Dent, which seemed such a slog the previous day, appears insignificant in such exalted company. Buttermere and Crummack Water are laid out, with Haystacks, High Crag, High Stile and Red Stile lined up in order. Down below, Honister slate mines spread their grey waste across Fleetwith Pike.

This point marks a clearly defined transition from the solitude and wilderness of Ennerdale to the full-blown tourism machine that is the Lake District. For the next few miles, I left the realm of the mountaineer and entered the world of the entertainment seeker. There was a steady stream of families and jeans-clad trippers dipping a toe in the soggy paths of the fells. Children raced each other to the top of the old tramway leading from Honister. Approaching the hause, a trundling Big Mountain Mine Bus belched its fumes as it conveyed hard-hatted visitors to the slate mines.

Climbing Honister Pass, vintage motorbikes ridden by veteran motorbikers rode in convoy, leaving in oily wake saloon cars with bored-looking children and teenagers gawping up at the towering crags.

The descent into Borrowdale was, for the most part, on an old cart track parallel to the metalled road. Approaching Seatoller, the track dives into Johnny’s Wood, with strollers galore. There’s even a tame, mini via ferrata with a chain bolted into rocks to aid less sure walkers in their efforts not to fall into the beck. Perhaps this was the inspiration for the Honister slate mine owner’s via ferrata hundreds of feet higher up.

The Coast-to-Coast follows a roundabout route through Rosthwaite, so you can get an ice-cream before going round the back of the houses to start the trek alongside Stonethwaite Beck. Eagle Crag loomed large, but looming even larger in the psyche was the towering height of Greenup Edge. This I had to surmount and it had been a long day.

The Coast-to-Coast follows a roundabout route through Rosthwaite, so you can get an ice-cream before going round the back of the houses to start the trek alongside Stonethwaite Beck. Eagle Crag loomed large, but looming even larger in the psyche was the towering height of Greenup Edge. This I had to surmount and it had been a long day.

Looking north down Greenup Gill

The campsite under Bull Crag was busy with families in their multi-room tents and children chirped and screamed as they splashed in the beck. But it wasn’t not for me: my campsite would be quieter and more secluded. I just had to get up to it.

Greenup Edge is a big drag, especially at the end of the day, and saves its hardest gradient almost till last, with a steep clamber to the side of Lining Crag. But the views from the top were spectacular, even if I was a little too on the gasping side of exhausted to appreciate them. To the North, Skiddaw and the Galloway Hills could be seen; High Raise filled the foreground while the Scafell range, Great Gable, Grasmoor and Robinson were all on view. Greenup’s glacial bowl was filled with drumlins picked out in the evening light.

There was a lot of wet ground to cover before a modest rise to the col at the head of Far Easedale. A few hundred metres’ walking and I found my pitch, a narrow spur with waterfalls either side. Up went the tent: a blissful view eastwards down Easedale and an even more blissful feeling as the boots came off.

I was a little short of my distance but I had a perfect home for the night. Not for me the throngs of Grasmere in search of Wordsworth’s inspiration: much better a night on the fells in the spirit of Coleridge. And Easedale is a beautiful valley.

Today’s journey was a trip from wilderness to tourism heaven (or hell, depending on your view) and back to serenity. I slept well.

Far Easedale to Riggindale

Warm sunshine greeted me as thin wisps of cloud cleared from the tops of Helm Crag and Gibson Knott. After the usual struggle to pack everything into the rucksack, I set off down Far Easedale, bound for Grasmere.

Warm sunshine greeted me as thin wisps of cloud cleared from the tops of Helm Crag and Gibson Knott. After the usual struggle to pack everything into the rucksack, I set off down Far Easedale, bound for Grasmere.

There were a few wild campers en route, enjoying the experience of waking up in the scenic joy of Easedale. It’s an odd experience to be walking down into a Lakeland village in the early morning, when so often it’s the opposite way.

Grasmere was to be a major refuelling stop, with shops, toilets and all the hustle and bustle of a Lakes honeypot. A bacon sandwich from the village bakery made a welcome breakfast.

Out of Grasmere, Tongue Gill is a relentless slog on its climb up to Grisedale Hause. By Grisedale Tarn, the sunshine had gone and a steel-grey mist had descended across the water. The route is a busy one, and a chance for a chat with a pair of fellow Coast-to-Coasters who were taking a more leisurely pace and having their gear transported by Sherpa Van. I looked, they said, as if I had my house on my back. Which I had.

The route follows the whole length of Grisedale before re-entering Ice Cream Land at Patterdale. This is the final chance to replenish supplies before Shap. There were camping facilities and B&Bs, but my home for the night was to be in the hills.

I had a vague idea that Angle Tarn might be a good place to stay the night, having fond memories of swimming there on a particularly warm summer day, but before that lay a big climb.

There are odd spots of relief from the climb up from Patterdale, and on a good day you will have lots of company as day walkers make their way up to the tarn.

The little tarn, with its miniature islets and inlets, was less than enticing on this day; the strong winds and thick mist made the afternoon feel like November rather than August, and I decided to walk on and find somewhere at a lower altitude.

Navigation requires care in bad visibility on complex terrain. I decided to duck off the high ground after Kidsty Pike and find a spot to pitch the tent in the remote valley of Riggindale.

The descent from Kidsty Pike was difficult, but the overnight stay in Riggindale was fantastic. The only disappointment was not having the company of the valley’s most famous resident, the golden eagle. There was, however, a sizeable herd of red deer barking and running across the dale, cautious at the rare intrusion of human activity into its territory.

The descent from Kidsty Pike was difficult, but the overnight stay in Riggindale was fantastic. The only disappointment was not having the company of the valley’s most famous resident, the golden eagle. There was, however, a sizeable herd of red deer barking and running across the dale, cautious at the rare intrusion of human activity into its territory.

Early morning cloud starts to clear in Riggindale

After the gloom and wetness of the previous day, it was great to wake up to sunshine. The sun would be my constant companion on virtually every day from now on.

Riggindale to Raisbeck

Haweswater is long; bloody long! The path overlooking the reservoir, which provides for the thirsty souls of Manchester, seems to go on forever and is massively overgrown in parts. Bracken chokes the path, as Wainwright remarked, and things haven’t improved since then.

Burnbanks was, apparently, a village built for reservoir workers but now seems to be being transformed into a strange, not quite gated, community and is very spic and span.

The transformation from the roughness of the Lakeland fells to the rolling pastures leading to Naddle Bridge is abrupt. There was an ambivalence to the leaving of the Lake District. Lakeland undoubtedly has the jewels in the Coast-to-Coast crown with its landscape and there’s a sense of anticlimax to the sight of green meadows and cultivated villages. But there was also relief at the thought of easier terrain with 18kg on my back and feet that were already feeling the strain.

The walk to Shap Abbey was a nice interlude and the sight of the ruin and – during my visit – the scores of sheep being brought into its neighbouring farm, made a pleasant stop to kick off the boots. I had now scheduled regular ‘boots-off’ breaks of five minutes to give the aching feet a chance of seeing daylight and having a temporary recovery.

The walk to Shap Abbey was a nice interlude and the sight of the ruin and – during my visit – the scores of sheep being brought into its neighbouring farm, made a pleasant stop to kick off the boots. I had now scheduled regular ‘boots-off’ breaks of five minutes to give the aching feet a chance of seeing daylight and having a temporary recovery.

Shap village, straddling the once manic main road north, the A6, is now a peaceful place and provides a refuelling stop. There’s a Co-op and, no doubt frequented by Wainwright, a fish shop.

Stocked up with fresh provisions, I settled down at the side of the bridge crossing the West Coast Main Line, only occasionally disturbed by the infrequent passing of a Virgin express.

That other main transport artery, the M6 was soon crossed (by a footbridge, you’ll be happy to learn) and an even more remarkable transport display: the dump trucks of Hardendale Nab Quarry. These goliaths of the trucking world thundered up and down the access track on their big balloon tyres, like some crazed, overexuberant juvenile mammal. They threw up huge clouds of dust from the unsurfaced track before disappearing into the portals of the quarry.

Take care crossing the track!

The quarry traffic is a stark reminder of the change in geology. From the ancient volcanic realms of the Lake District, I had now passed into limestone country, and the pale, grey rock would be under my boots for the next three days.

The plateau between Hardendale and Orton was a surprisingly pleasing section. It’s easy walking, with good views backwards to the increasingly distant shape of Kidsty and her Lakeland companions, and the shapely northern slopes of the Howgills occupying the southern horizon. It’s an area few would dream of visiting: sandwiched between the grandeur of the Lakes, the beauty of the Dales and the bleak wildernesses of the Howgills, it’s a pleasant little jewel.

The wide open spaces of Crosby Ravensworth Fell, between Shap and Orton

And that’s one of the great attractions of setting your stall out to walk the breadth of the country. You have to walk through all the countryside and, along the way, you’re going to encounter those little English gems that get overlooked by nearly all the routefinders and guide book authors. I loved this little stretch.

Orton village can be bypassed, but I wanted to get some food for the next day, so dipped down into the neat little settlement, arriving at 6.15pm, to be told by a group of residents that the post office closed at 6pm. So be warned: don’t delay getting to Orton if you want to eat. There is a pub in the village, the George Hotel, and the place has a very friendly feel. There’s even a chocolate factory if you hit the village in time. But it was onwards to the campsite at New House Farm, two kilometres of painful asphalt walking, and the increasing realisation that heavy boots were not the ideal footwear for this trip.

New House campsite is sparse: toilets and showers are in makeshift portable cabins and, for some reason, there appears to be a letterbox between cubicles which affords perfect views, should you require, of the neighbouring occupant’s genitalia. Perhaps it’s an odd Westmorland custom.

The site is flat, with beautiful view south to the Howgills – pricey at £6 for such a basic setup, though I did get a mug of milk from the farm for 10p.

Raisbeck to Keld

The better mathematicians will work out that, on a ten-day walk, day five should land you at the half-way point. That was the goal for Thursday, but there was a lot of making up to do. Progress over the fells of the Lake District had been slower than I wanted and now a long day lay ahead.

The day dawned gloriously and I hit the road before eight o’clock. Bypassing the reedy shores of Sunbiggin Tarn, the featureless moorland of Ravenstonedale has as its constant, distant companion the rolling folds of the Howgills. At the summit, the next major waypoints appeared: the hills of Kirby Stephen, Baugh Fell, Wild Boar Fell and our next target, Nine Standards Rigg.

The cairns of Nine Standards Rigg, overlooking Kirkby Stephen

The cairns of Nine Standards Rigg, overlooking Kirkby Stephen

Care is needed navigating around the ancient Severals Settlement. Pay heed to the map and the guide book and the way will lead you down to the disused railway track bed, complete with derelict cottages and overbridge. It’s easy to imagine, still, a little steam engine puffing busily along this route, disgorging its passengers at tiny country stations along with milk churns and bundles of post.

Soon, the still thriving Settle to Carlisle line is met, with a dark underpass leading on to the back ginnels of Kirkby Stephen.

Encountering a busy little town such as Kirkby en route is a jolt to the solitude encountered on the fells and moors. It’s quite a bustling place, with a Spar shop, Co-op, toilets (very important for Coast-to-Coasters!) and a youth hostel, now run independently.

There’s also a delightful riverside area which made a perfect site for picnic lunch, with children throwing stones into the River Eden and ducks begging for food.

The ravages of quarrying here have carved out a huge section of the hillside and, after passing through the picturesque hamlet of Hartley, its quarry fence was the handrail for the steep road climb up towards the beckoning cairns of Nine Standards Rigg.

The rigg represented the last ‘big’ climb before the Cleveland hills, and it was warm work in the August heat. From the top of the hill, the Pennines fell away abruptly to the north, into the wide plain of the Eden Valley, overlooked by their highest point, Cross Fell.

The cairns of Nine Standards came into view and then disappeared repeatedly as the slacks and brows were traversed. Even until the last ten metres rise the prominent piles were hidden from view. From the summit, there were fine view of Cross Fell and Great Dun Fell and beyond to Scotland and the Galloway coast, back westwards to the prominent peaks of the Lake District: Great Gable and the Scafell range and south-west to Wild Boar Fell. Eastwards lay the Dales hills yet to be encountered.

As Wainwright pointed out, Nine Standards Rigg is the watershed. Everything from now on flows east, so off I set. There’s a view indicator built by the Kirkby Stephen fell rescue team to commemorate the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The memorial has already outlasted the marriage and the life of one of the parties and now stands as a historical oddity.

Say goodbye here to the distant Lake District fells, on view on the western horizon.

Nine Standards Rigg flatters to deceive. Its fine ridge with its craftsman-made monuments soon degenerated into a glutinous morass, in the worst section of the whole route. There are three different, colour-coded routes, designed by the authorities to minimise erosion across the peat bog. The whole area is Countryside and Rights of Way access land but, in my view, the direct, eastwards path towards the head of Witsundale, which is the August to November route, is probably best avoided if there has been any great amount of rain.

Even in the warmth of the August sun, the bogs are unavoidable and you will inevitably end up caked in mud and with wet feet. The alternatives head south towards the Birkdale road.

Witsundale is a beautiful, secluded valley which would be a joy if it didn’t come at the end of a long, hard day when all you want to do is collapse into your pit. One to be revisited when a little fresher.

Eventually, and to my relief, the campsite at Park House, Keld, hove into view. Be warned that the former youth hostel in the village is now a restaurant, so if you were expecting a bed for the night, it’s more likely to be a bed of wild rice than anything you might use for slumber.

Day Five was a long day, but it put me back on schedule. The time and distance lost over the hard ground of the Lake District had been regained and – I was at the half-way point.

There’s a friendly atmosphere at Park House. £4 will get you your pitch for the night and there’s a barn in which to cook and eat and escape the clouds of midges!

Keld to East Applegarth

Another cloudless dawn and warm sunshine for Day Six. On with the sun lotion and out with the new map. A spring in my step, at least until the pain recurred, and the prospect of a traverse of virtually the whole of Swaledale.

Another cloudless dawn and warm sunshine for Day Six. On with the sun lotion and out with the new map. A spring in my step, at least until the pain recurred, and the prospect of a traverse of virtually the whole of Swaledale.

For about 100m, the route is in the company of the Pennine Way, which then heads north as the Coast to Coast aims east to the abandoned mines of upper Swaledale.

The high-level route, which I took, avoids the meander along the valley bottom. Though more strenuous, it is, I think, more rewarding. It is a walk through the industrial past.

From the abandoned ruin of the fabulously named Crackpot Hall, the Coast to Coast makes its way through mining history. At one time, this area would have rivalled the old coalfields of south Yorkshire for activity. Everywhere are the remnants of mankind’s efforts to exploit the geology of Swaledale.

The route is quite tough, with Swinner Gill and Bunton Hush providing energy-sapping ascents out of deep gills. There are lots of deserted old workings and buildings to explore, so don’t expect to make rapid progress.

Eventually, the archaeology of the 18th and 19th centuries is left behind and the culture shock of Reeth appears.

Reeth is a tidy little village, with craft shops and a multitude of Dales day-trippers. I found the contrast between the desolation of the mines and the chocolate-box primness of the village marked.

Bizarrely, when you consider the hundreds of square miles of prime countryside surrounding Reeth, visitors had paid to park their cars on the village green and get out their folding chairs and picnic, a foot away from their motoring neighbour.

I don’t suppose the picnickers of Reeth would ever comprehend why a walker should tackle something like the Coast to Coast and, quite frankly their idea of Dales leisure was beyond me too.

I kept walking.

Beyond Reeth lay Marrick Priory, founded between 1154 and 1157 and vandalised sometime in the 20th century by the addition of a brutalist new building in the name of outdoor education. Between them, Henry VIII and the Diocese of Ripon have done a fine job of ruining the priory.

Onwards and upwards to the hamlet of Marrick: I had a rendezvous to fulfil.

Dave the Postman had implored me to call at Elaine’s tea room in the very first hour of my walk and who was I to disobey? The tea room is actually at Nun Cote Nook, beyond the hamlet and just a hundred metres or so off the Coast to Coast.

A glass of orange juice and an ice cream were supplemented by a top-up of my water bottle, just as the postman arrived. I have no idea why his round takes him to this isolated farm at four in the afternoon, but it was nice to see Dave again, six days and 110 miles after our first brief encounter on the cliff-tops of St Bees.

Elaine also informed me that it is possible to camp there, which is useful to know, as it is not marked on the maps as a campsite.

However, I wanted to put a bit more distance in, so it was off towards the village of Marske and my eventual stay, the only one of the trip with a roof over my head.

However, I wanted to put a bit more distance in, so it was off towards the village of Marske and my eventual stay, the only one of the trip with a roof over my head.

The cattle stalls have been retained at the bunkhouse at East Applegarth

East Applegarth bunkbarn is a pleasant building fashioned out of an old milking parlour on the farm. It still has its stalls and the bunks are laid out between them. It has great views over Swaledale and a little kitchen with cooker and crockery. There’s a shower and, best of all, the knowledge that you don’t have to strike camp in the morning.

Buzzards have returned to the farm after the hiatus of the 2001 foot-and-mouth disease, and there are swallows galore too.

By now, one slight niggle was apparent from the Coast to Coat route: because I was walking in, generally, the same direction, my ‘southern’ half was getting all the sunburn while my ‘northern’ side was much less affected. Perhaps I should walk backwards tomorrow.

The departure from East Applegarth marked the point where all the views are eastwards. The flat lands of the Vale of Mowbray are laid before the walker and beyond them, the final high ground of the route, the North York Moors.

East Applegarth to Danby Wiske

Day Seven marked the end of the Yorkshire Dales section and offered the chance of a day’s worth of easier terrain across the plain beyond Richmond.

Day Seven marked the end of the Yorkshire Dales section and offered the chance of a day’s worth of easier terrain across the plain beyond Richmond.

Richmond itself feels like a metropolis after so long spent in the remote uplands. Its castle dominates and the whole place has a very busy feel. There’s a big Co-op at which I stocked up with food and, if you had the time, you could easily spend a day there.

But progress was the name of the game and, suitably replenished, I made my way across the River Swale and out towards Wainwright’s hated flatlands.

There is no way of avoiding the plains east of the A1. The Vale of Mowbray, the northern extension of the Vale of York, is bereft of contour lines. Unfortunately, whoever devised the topography of northern England at this point forgot to put in the hills.

Whereas the crossing of the other main road north, the M6, in Cumbria, is by a soaring footbridge affording views not only of the rushing traffic, but of the surrounding countryside, the traverse of the A1 is via a murky concrete underpass shared with the River Swale.

Both lanes north on the dual carriageway were stationary when I passed under the road, which seemed indicative of the pace around here. No galloping becks tumbling down hillsides; just meandering, semi-stagnant water courses idling their way vaguely eastwards.

At Bolton-on-Swale I encountered only the second Coast-to-Coasters – a couple doing the route east to west, sitting having lunch at the entrance to the village. Unlike the West Highland Way, where every second person you encounter seems to be aiming for Fort William, I came across few people tackling the route. Maybe it was the fact it had been a dreadful summer, or perhaps I was out of kilter with the normal pacings of C to C-ers, but I was surprised by how few fellow travellers along the Wainwright route I came across.

The guidebooks warn of the paucity of camping opportunities in the Vale of Mowbray – with one exception: the White Swan at Danby. I had, according to the advice, phoned the pub ahead to warn them I wanted to camp in their beer garden and been told that, yes, camping was fine, but there would be no food available because there was a wine-tasting evening that night. Hence the top-up of provisions at Richmond.

The White Swan is a place of legend on the Coast-to-Coast forums. The place, for some reason, evokes controversy and is, depending on who you believe, the worst pub in Christendom or the best place to spend the night on the whole route.

I hoped it was the latter.

After a week on my feet, the going was getting easier, both by dint of increased fitness but also of course, because the terrain was so flat. However, the toll on my feet was telling and I was cursing the decision to wear my heavy Scarpas.

Navigation through the barley and vegetable fields is not always easy, and I found Terry Marsh’s guide book invaluable with his detailed directions through the hedgerows and furrows of this arable area.

Wainwright suggests putting your best foot forward by keeping to the roads, but it’s worth seeking out the field routes for two reasons: the toll on the soles of your feet will be less; and, the volume and speed of traffic along the country lanes has undoubtedly increased since he wrote his guide, and road walking is not a pleasant experience, in my view.

First impressions of the White Swan were not good. I’d been given instructions where to pitch the tent if the licensees weren’t about – which they weren’t.

I put up the tent on the beer garden – nice and flat, if a little incongruous after the wild camps of Easedale and Riggindale.

On venturing into the pub I found a toilet with a broken light, no toilet paper and in fact, as I noted at the time, bugger all really.

However, once Paula and Terry, the publicans, arrived, things started looking up. They were lovely people who couldn’t do enough. The campers’ toilet and shower were in much better state once they’d been opened up and Paula did actually offer to knock up some food for me if I wanted it.

The evening was interesting, with a seemingly vast quantity of bottles on offer for the small crowd of locals who had signed up for the wine-tasting. A very jolly pub and very welcoming. Camping will cost you £5 and it is, with the exception of the guest house next door, just about the only place to lay your head in the area.

Danby Wiske to Lord Stones

Setting off from Danby Wiske, the Cleveland Hills – my next objective – looked quite distant but, after wending my way through the fields and hedgerows of the plain, suddenly the hills seemed closer and the most dangerous hundred metres of the walk approached: the A19.

Setting off from Danby Wiske, the Cleveland Hills – my next objective – looked quite distant but, after wending my way through the fields and hedgerows of the plain, suddenly the hills seemed closer and the most dangerous hundred metres of the walk approached: the A19.

My third encounter, of sorts, with Coast to Coasters was just east of Danby Wiske. Two Australians, armed with Paul Hannon’s book, were navigating an alternative route, starting in Arnside on Morecambe Bay and ending at Saltburn. It misses out the high ground of the Lake District, passing instead through the western Yorkshire Dales and joining the more conventional route at Keld.

The man in the pair was complaining of blisters after getting soaked feet while attempting to do the walk in trainers.

In the midst of the flatlands, the orchards of the ruins of Brecken Hill Farm provided an unexpected feast of damsons.

By now, despite the fruit top-up, I had run very short of food, so the filling station at the side of the A19 provided a stop gap chance to buy some chocolate until I could get some more substantial provisions. It also gave me chance to steel myself for the most dangerous 30 seconds of the whole ten-day venture.

The A19 dual carriageway carries a steady stream of traffic to and from Teesside, all at 70mph or more. With aching feet and a heavy backpack, the crossing of its two carriageways is a nightmare.

It took me probably five minutes waiting for anything like a safe gap in the thundering traffic to get to the central reservation, and then a similar time to negotiate the southbound section. If any of the route cries out for a footbridge, this is it!

Many Coast to Coasters stay the night at Ingleby Arncliffe or Ingleby Cross, but I wanted to get up on to high ground to find somewhere to pitch my tent.

The ascending track through Arncliffe Woods was home to dozens of baby pheasants, most of which seemed unaware of the dangers posed by their main predator, man, and seemed curiously tame.

The route doubles back at the edge of the wood to continue north-easterly towards Scarth Wood Moor, but I needed to get food, so a diversion to Osmotherley was necessary. The town is the gathering point for the start of the Lyke Wake Walk, a long-distance challenge following the old coffin route across the North York Moors and is traditionally started in the dead of night.

Which, in my view, is probably the best time to visit the place. Osmotherley oozed a smug affluence; the BMW quotient is high and its once idyllic streets were throng with day-trippers. Slacks and Sunday casuals were in abundance and tea-rooms seem to have taken over the village. The only genuine shop, the post-office cum newsagent cum general store was up for sale.

Osmotherley typified everything which is wrong with rural villages in today’s world. I hated it.

Watered, stocked up and fed up, I left the place and headed back to the serenity of the Cleveland escarpment and into the switchback section of the route across the North York Moors.

The view from the escarpment is quite extraordinary, with the massive flat Cleveland plain stretching to the belching chimneys and chemical stacks of Teesside. North of that, the Victorian folly of the Penshaw monument is clearly visible. To the west, the hills of the Cheviot rise on the horizon and there is a fine retrospective panorama of the Yorkshire Dales, stretching right down to their southern peaks.

The true start point of the Lyke Wake Walk was then passed, the trig point on Beacon Hill, and the purple heather of the moors lay stretched out for miles.

The true start point of the Lyke Wake Walk was then passed, the trig point on Beacon Hill, and the purple heather of the moors lay stretched out for miles.

Scarth Wood Moor

Then, like an excited child on a trip out with parents, I saw the sea. The North Sea! Admittedly, the view was blighted by the accompanying horrors of Middlesbrough and Redcar, but it was the still a fillip late in the day to realise that the end was in sight, or at least the coast a few miles up from the end.

With it, of course, came a slight sadness that accompanied the realisation that the great adventure was not far from over.

The route continues over Live Moor then rises to flank the unexpectedly sited gliding club runways on Carlton Bank. It was now getting quite late and I still hadn’t found a site to pitch my tent.

Then a chance encounter with a hangliding enthusiast saved the day. As I walked down with him from an aborted trip to the top of Carlton Bank – it was too windy to fly – he mentioned there was a cafe in the woods at the foot of the moor and the owner would let you camp in the grounds, as long as you used his cafe.

And so I discovered Lord Stones.

Lord Stones is an oddity run by the eccentric John Simpson, a man who seemed irritated by the fact that so many people wanted to eat in his cafe when all he wanted was a quiet life. The cafe itself is in the style of a bunker, built into the undulations of the hill. That makes is sound a little unpleasant; it’s not.

Mr Simpson is a curious mixture of altruism and paranoia. His cafe walls were plastered with invective letters written to the Northern Echo bemoaning the fact that the British countryside was run by left-wing quangos.

Lord Stones had a family of swallows nesting on the door frame of the ladies’ loo and Mr Simpson had set up a webcam so visitors could view the antics of the birds. Stop sniggering; it was all very decent.

Lord Stones had a family of swallows nesting on the door frame of the ladies’ loo and Mr Simpson had set up a webcam so visitors could view the antics of the birds. Stop sniggering; it was all very decent.

Mr Simpson also explained he had hand fed the chicks when the parents had decided to desert them for days on end.

For some reason, despite myself, I quite liked Mr Simpson. But I kept politics off the menu. However, the first plate of chips on the whole walk was very welcome and I pitched my tent on an open stretch of springy grass with a fantastic view of the shimmering lights on the plain below.

Be warned, however, that the cafe is popular with bikers, so if your visit coincides with one of their camping weekends, you may not get much sleep.

And yes, it is free to camp. Sshh, don’t tell anyone!

Lord Stones to Grosmont

The route after Lord Stones continued along the edge of the Cleveland escarpment, and is, well, quite hard work, after the flat lands of the Vale of Mowbray, the extensive arable fields of which still stretched backwards towards the hills of the eastern Dales.

The route after Lord Stones continued along the edge of the Cleveland escarpment, and is, well, quite hard work, after the flat lands of the Vale of Mowbray, the extensive arable fields of which still stretched backwards towards the hills of the eastern Dales.

The lights of Teesside dominate the night-time view from the campsite at Lord Stones

The Coast-to-Coast walk clambered over, in succession, Kirby Bank, Broughton Bank, Hasty Bank and the boulder outcrops of the Wain Stones, Clay Bank before finally the escarpment is left and the path takes a route to the south across Urra Moor.

It was time to say farewell to the belching towers and stacks of Teesside and head towards the easy walking of the North York Moors. Urra Moor was a relief to the legs and lungs after the sharp ascent and descents of the banks and gullies which cut across the edge of the escarpment.

There was also an almost tangible feel that the end was nigh. I couldn’t quite reach out and touch the villages of the North Yorkshire coast, but that glimpse of the North Sea around Saltburn had changed my frame of mind. I imagined how a horse must feel as it reaches the final furlong.

My rucksack weighed as much as a small jockey (well, half of one, maybe) and my feet felt like they’d been trampled on by the field from the Grand National, but I could almost smell the salty seaside air.

The route encounters a few railways en route, from its starting point just a few hundred yards from the level crossing at St Bees. There’s the West Coast Mainline; the Settle-Carlisle line and its associated disused trackbeds around Kirkby Stephen; the East Coast Mainline and the route from Northallerton to Middlesbrough, but the one under my feet was probably the most remarkable of them all.

The Rosedale Ironstone Railway forms the route for the next 8km (5 miles). Its rails have long gone, but the contouring snake of its hardcore bed lead improbably across the moorland until it reaches the Lion Inn near Rosedale Head.

The Rosedale Ironstone Railway forms the route for the next 8km (5 miles). Its rails have long gone, but the contouring snake of its hardcore bed lead improbably across the moorland until it reaches the Lion Inn near Rosedale Head.

The former railway, built as its name suggests, to carry iron ore from the moorlands to the Teesside furnaces, offers a circuitous but easy walk over the broad expanses of Farndale Moor and High Blakey Moor. This implausible route made for rapid progress.

The Lion Inn is a food pub if you need to top up the calories. If water’s all you need, which is quite probable after a traverse of the moors sparse in running water, there’s a tap on the outside wall.

A short section up the road after the Lion Inn is unpleasant but there is a short cut across the moorland bowl part way up, heading towards the large Fat Betty stone, marked White Cross on the maps. Wainwright preferred to stick to the road; I didn’t – I’d rather have bog than exhaust fumes.

There was another reminder of the end of the route as the path crossed Danby High Moor. The North Sea now filled the eastern horizon, from Redcar southwards, the cargo ships and oil tankers clearly visible out to sea.

This penultimate day was to be a long one; I wanted to put myself within easy striking distance of Robin Hood’s Bay, so Glaisdale was swiftly passed. Once again, I was too late to take advantage of the post office and butcher’s shop though I could, had the fancy taken me, have caught a performance at the village theatre. I decided against and pressed on towards Grosmont.

A short break on one of Glaisdale’s roadside benches set me up for the final push, through the woods to Egton Bridge and the last 2km (1 mile) to Priory Farm, at the entrance to the village of Grosmont.

The farm has rudimentary camping, but I paid my £3 and had the field to myself. But there is a shower, a little kitchen area and, useful at this point, somewhere to charge my phone, as the wind-up charger was not doing its job properly.

The night brought a sound to which I had grown unaccustomed: rain on the tent. Not much, but enough to ensure a little extra weight in my rucksack as I packed away the thing wet.

Grosmont to Robin Hood’s Bay

The steam engine was being stoked up ready for a day’s work on the North York Moors Railway as I went through the village, but the post office was bereft of bread and I couldn’t wait for the baker’s van to call, so I set off with no provisions, a decision I would regret later in the day.

The steam engine was being stoked up ready for a day’s work on the North York Moors Railway as I went through the village, but the post office was bereft of bread and I couldn’t wait for the baker’s van to call, so I set off with no provisions, a decision I would regret later in the day.

The road out of the village boasts one of the steepest metalled roads in the country, at 1 in 3, and it was a relief when it finally started to ease as Sleights Moor was reached.

The coast was calling. Day Ten would be the day the boots would be splashed by the spume from the North Sea, but already I was regretting not stocking up on food. There wasn’t a single place to buy anything to eat and even the year-old emergency chocolate had been devoured the night before.

Trying to put the hunger out of my mind, I set off across the busy Whitby road and down into Littlebeck, a charming little village deep in a valley hidden from the thousands heading along the road towards the fish-and-chips delight of Whitby.

An impatience had taken over me and the woods south of Littlebeck seemed to go on for too long. I felt I needed to see the sea again, and these sylvan charms which, at any other time would have made a lovely walk, were just an obstruction to the final goal.

The remarkable hand-hewn rock shelter of The Hermitage, in the middle of the woods, provided some interest. Wainwright makes little of this oddity, but Terry Marsh informs us that it was created in 1790 by George Chubb as something to keep him occupied. Few other facts seem to be known about this extraordinary edifice, which has seats carved into its interior and would make an ideal lunch venue, for those who had food.

The remarkable hand-hewn rock shelter of The Hermitage, in the middle of the woods, provided some interest. Wainwright makes little of this oddity, but Terry Marsh informs us that it was created in 1790 by George Chubb as something to keep him occupied. Few other facts seem to be known about this extraordinary edifice, which has seats carved into its interior and would make an ideal lunch venue, for those who had food.

The Hermitage, carved by hand from a single boulder

Unremarkable moorland, boggy in parts, followed, after rising from the Little Beck valley, with the reward of Whitby filling the horizon, though Robin Hood’s Bay was still out of view. The sheltered village which marks the end of the Coast-to-Coast Walk keeps itself hidden until almost the last mile.

Another road crossing at Hawsker was the last one of the walk. Someone had tossed a newspaper out of a passing car and its headlines brought home a world to which I had been oblivious for the last ten days. For all I knew, there could have been a new monarch, the discovery of a cure for Aids and Alfred Wainwright’s unexpected rise from the dead. Walking through northern England’s finest scenery is the greatest tonic for a world-weary traveller. You inhabit your own world; the most important thing is finding the next footpath; the next meal; a place to lay your head. I recommend it!

There’s a curious feel to the last few miles of the route. It passes through the massed ranks of the caravans of Hawsker Bottoms, a surreal, neat, false world a million mental miles from the wilds of Ennerdale, Nine Standards Rigg and Gunnerside. But there was a shop!

Never was a plastic wrapped chocolate muffin more welcome. That, and two bars of chocolate would be my reward for gaining the North Sea coast at the spectacular little cove at Maw Wyke Hole. It really was a fantastic feeling to have made the east coast and I felt an urge to tell everyone just how far I had come. I resisted the urge, but it wasn’t easy.

The final 5km (3 miles) of the Coast-to-Coast walk follow the cliff-top path which is used by many taking short strolls. Robin Hood’s Bay itself remains hidden until Ness Point is reached, then the pantiled roofs of the town come into view and the journey is nearly at an end.

The final 5km (3 miles) of the Coast-to-Coast walk follow the cliff-top path which is used by many taking short strolls. Robin Hood’s Bay itself remains hidden until Ness Point is reached, then the pantiled roofs of the town come into view and the journey is nearly at an end.

There was a certain amount of mental adjustment needed as I gained the road leading steeply down to the bottom of the town. Despite its small size, Robin Hood’s Bay is very definitely a seaside place, with the attendant gift shops, ice-creams all the other panoply of a coastal resort.

After so many days of solitude, wilderness and beautiful countryside, it felt a strange world.

But there it was: the North Sea, lapping up the slipway next to the Bay Hotel. I dropped my burdensome rucksack and stepped into the foamy water, letting my boots soak for a minute or two.

And then, it was the fulfilment of the other requirement of every true Coast-to-Coaster: a pint in the Bay. It’s a hell of a way to walk for a decent pint, but it was worth it.

The pub has a book for completers to sign, and you can pay for a certificate or even buy a tee-shirt. That bit’s not compulsory, but I got a certificate anyway.

The pub has a book for completers to sign, and you can pay for a certificate or even buy a tee-shirt. That bit’s not compulsory, but I got a certificate anyway.

A piece of paper is fine, but what you should be left with after walking 192 miles across the country is a set of memories that will stay with you for a long time. The pain, the joy, the sunshine, the rain. But above all, the knowledge that you’ve completed probably one of the best walks in the country and maybe in the world.

The Bay Hotel: end of the road

Britain’s only a small place, but it has some fantastically varied sights and the Coast to Coast will take you through plenty of them.

- Highlight: Ennerdale – it’s just a shame it comes so early in the walk.

- Low point: the bogs of Nine Standards Rigg.

Guides:

A Coast to Coast Walk by A Wainwright Frances Lincoln

A Northern Coast to Coast Walk by Terry Marsh Cicerone

Coast to Coast Walk: 190 Miles Across Northern England by Paul Hannon Hillside Publications

Maps:

Harvey Maps publish the Coast-to-Coast Walk in two sections at 1:40 000

The Ordnance Survey strip maps of the Coast-to-Coast Walk are now out of print, but the whole route is covered by either the 1:25 000 Explorer series or the 1:50 000 Landranger series

Baggage carrying and accommodation booking

Sherpa Van Project

Brigantes

Coast to Coast Packhorse

Coast to Coast Holidays

Accommodation

Doreen Whitehead, of Butt House, Keld, Richmond DL11 6LJ, publishes an annual guide to accommodation on the route. You can contact her on 01748 886374.

Guest

31 July 2008I have just finished the c2c with my wife and reading your account has reminded me of the joy and sense of achievement. I would like to update your comment about Keld Lodge. Indeed they do have a very good restaurant, they also do b&b which my wife and I enjoyed very much, during our stay there we were told by Tony at Keld Lodge that the also own Butt House. Pete

Willie Lees

12 September 2008I enjoyed reading this account though it makes me glad that I'm doing the walk without having to carry all my gear and that I'm not camping. I cannot wait to get started on 24/9/08. I have never done a trail walk before and the fact that I am walking for charity is an added incentive.

George Glass

14 October 2008I did this walk with my wife just after Wainwright published his Coast to Coast

book,no well warn paths or obliging native traders then.However having seen and traveled a great deal of the world since then I know realise it is one the best of all the world's walks.It has the best scenery and recorded history in the world.We should leave out the early school trips to nations on the continent and let our children first appreciate the absolute beauty of these special islands we inhabit.

Jez Brown

09 October 2012Absolutely brilliant, thank you for taking the time to share your experience. My wife and I are planning to set out on this journey as soon as we are able and like yourself will be taking a tent as in my opinion it is the best way to fully appreciate the wonderful solitude and joy of been close to nature.

Dave Johnson

21 January 2014Great article. I did the C2C E2W in 2011 and will surely do it again. Reading this brought back all the memories and more from such a fantastic walk. I fully agree with just about everything said, and especially that the Lake District is the highlight, in my view therefore it is an advantage to leave it till last, when the legs are fitter and the scenery can be appreciated far more. Additionally doing it E2W gets the Vale of Mowbray out of the way on Day 3/4. My other recommendation - St Sunday Crag is a suitable high level alternative to Helvellyn/Striding Edge if you are on your own carrying all you worldly goods.

Terri Stevenson

10 October 2014Really great article, I love this walk and have just completed it for the second time this September. The first time was in 2003 and a couple we met on that walk, and who have become great friends, completed the walk with us. My hubbie wanted to do something special to celebrate his 65th birthday and this walk is certainly special. We did it at a more leisurely stand and stare pace of 16days and we used the company Packhorse to transfer our baggage. We are so lucky in our country to get such a diversity of landscapes and while I love the Yorkshire dales and North Yorkshire Moors the Lake district is my favourite part of the walk.