Great Gable, Green Gable and Base Brown from Seathwaite

Note: groughRoutes should be used in conjunction with maps, a compass and other navigational aids. Routes often use access land and involve finding your route off footpaths. Knowledge of and competence in using a map and compass is essential when using the routes. Carry the correct equipment for the conditions and be aware of hazards in the outdoor and mountain environment.

This route up one of the Lake District’s most shapely mountains involves a little scrambling and a lot of hard work in an effort to get off the usual routes up the Gable. In mist, you must be able to navigate well. Don’t attempt the route if you haven’t a head for heights and aren’t prepared to do a little four-by-four work up and down the rocky sections.

Map: Ordnance Survey Explorer OL4, The English Lakes north-western area

A short walk, only 9.1km (5.6 miles), but with 1 250m of hard ascent. Allow six hours.

We start in Seathwaite, reached by taking the Borrowdale road down the Eastern side of Derwent Water then turning left just before the small village of Seatoller. If you’re approaching over the Honister Pass, turn right after passing through the village. Seathwaite does get busy, so it may be wise to try and get there fairly early, though there is room for a good many cars on the lay-by and verges before the farm buildings and turning circle.

The path (right) up the Climbers' Traverse from the stretcher box, with Tophet Bastion visible at top of picture

From the farm yard, take the path under the arch on the right and make your way across the bridge, turning left to follow the western side of the beck. The path soon starts to climb to the right, into Styhead Gill, with the waterfall of Taylorgill Force visible and audible. Alfred Wainwright asks the valid question of why, if the gill is Styhead Gill, the waterfall is Taylorgill Force. Answers, on the back of a £20 note please, to the grough editor.

The path up the gill is rocky, with some easy scrambling, but always with changing views of the waterfalls. As we near the top of the gill, the path veers to the left to a wall with a stile. Use this for a view from the small wood at the top of the force, with a fine grassy area for a break for a snack if you need to replenish the energy you’ve expended.

Continue back over the wall and up the north-west side of the beck. The gill levels out as it reaches Styhead Tarn and the population increases as we approach this popular meeting of the paths where Moses’s Trod, the route from Esk Hause and ours all come to a point at the mountain-rescue stretcher box.

Most of the ascenders of Great Gable will be using the ‘tourist path’ leading to the right, straight up to the summit. But we don’t want to go with the crowds, so we take the path diagonally to the left of the main path up, heading for the base of Kern Knotts.

The terrain soon becomes rocky and care is needed negotiating the boulders and rocks, as well as keeping track of the direction of the path. The south traverse we’re using came about as a rock-climbers’ path, giving access to the crags of the Great Napes and White Napes. The path gives great views of the looming Scafell massif, with Great End, Broad Crag and Scafell Pike seeming close enough to touch.

At NY 213 097 there is a small cave. If you’re short of water, fill up here: it’s the last you’ll come across for some time. Cross the base of the large scree chute Great Hell Gate and continue the traverse. Napes Needle, the rock pinnacle which is strictly the province of rock climbers, rises above the path. A diversion can be made to get a better view by taking the path forking up to the right.

It’s said that the first ascent of the Needle by Walter Parry Haskett Smith in June 1886 marked the birth of the sport of rockclimbing in Britain. His solo climb included throwing three pebbles on to the summit of the pinnacle to see if it was relatively flat and capable of offering a handhold. He said: “Out of three missiles one consented to stay, and thereby encouraged me to start, feeling as small as a mouse climbing a milestone.”

The account of his climb, in his own words, can be seen here. In modern terms, the climb to the top of the needle by the usual route, using the Wasdale Crack, is rated Hard Severe. New routes are still being posted, but one of the hardest manoeuvres is getting safely back down from the summit and involves setting up a belay before you step on to the top platform. All of which you can safely ignore and move on to our own ascent, by somewhat easier means, of Great Gable.

As we approach the second scree chute, Little Hell Gate, at the end of the Great Napes, an awkward step round a small buttress can be avoided by using the path slightly lower.

Picture, above right: looking down Little Hell Gap to Wasdale

Gird your loins and scramble up the loose stones and rock of Little Hell Gate, our route to the summit. It’s a case of three steps forward, two back as we scrabble up the steep scree. Where possible, use the firmer ground to the right. The Sphinx Rock (see picture, below left) is visible on the right soon after starting up the chute.

As you near the top of the gully, clamber right on to the top of the Sphinx Ridge, a broad, short ridge leading to the base of Westmorland Crags. The path steers us to the left, along the base of the crag, then upwards to visit Westmorland Cairn. From the cairn, move straight up the fall line on to the summit plateau and its cairn.

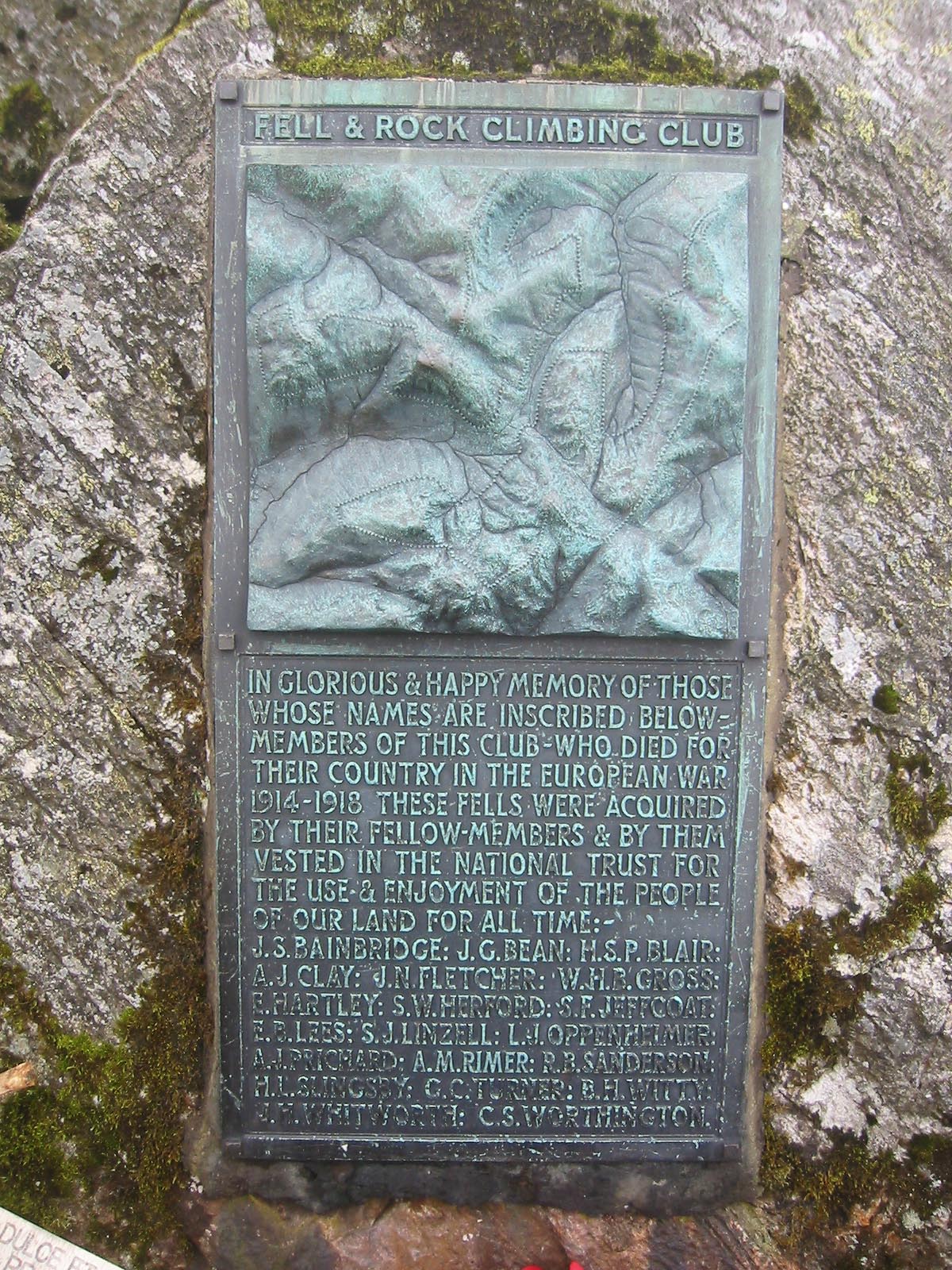

We’re now back in crowded terrain, but if you can find any peace, take time to read the inscription on the plaque erected by the Fell and Rock Climbing Club (FRCC) in memory of its members who died during the First World War and marking the fact that Great Gable was bought by the club in order for people such as us to enjoy. The plaque also has a relief map of the mountain and its surroundings.

We’re now back in crowded terrain, but if you can find any peace, take time to read the inscription on the plaque erected by the Fell and Rock Climbing Club (FRCC) in memory of its members who died during the First World War and marking the fact that Great Gable was bought by the club in order for people such as us to enjoy. The plaque also has a relief map of the mountain and its surroundings.

The plaque (pictured below) was dedicated on Whit Sunday, 1924 following a service at Coniston. The FRCC Journal of that year records: “If there is any communion with the spirits of dead warriors, surely they were very near that silent throng of climbers, hill-walkers, and dalesfolk who assembled in soft rain and rolling mist on the high crest of Great Gable. The gloom and gentle wind-sounds added impressiveness to the occasion. There was no effort at pageantry or emotion; the service was a tribute to memory.”

Two buglers from the St Bees’ School cadets played the Last Post at the end of the ceremony.

Great Gable is a very special mountain.

With the fate of mountaineers on your mind, make sure you leave the summit cairn in the right direction, for on three sides are precipitous crags to catch the navigationally challenged. So we’re taking the path that leads north for a short distance from the plaque before turning right towards the hause of Windy Gap.

The path drops down quickly, with Gable Crag to the left and we’re soon at the crossroads of Windy Gap. Black Sail youth hostel is visible down in Ennerdale, with Green Gable straight ahead and Brandreth to its left. It’s straight ahead and up the short 41m climb to the summit for our second ‘Wainwright’ of the day. Green Gable’s top is an inclined grassy summit ending in crags. There’s a small cairn and shelter. We need to get our summit paths right: one leads to Brandreth, the other to Base Brown. We’re taking the latter. In case of mist or befuddlement, get the compass out.

Don’t drop down into the Gillercomb hollow; keep to the broad col and the gentle rise, taking the path that leads slightly to the right, towards the summit.

In contrast to its rocky neighbours, this approach reveals Base Brown to be a featureless grassy mound though as we’ll find out soon, it’s not as innocuous as it appears. There are good views backwards to Great End, Great Gable and the Scafells, while Glaramara dominates to the East.

From the summit of Base Brown, follow the path north-eastwards to where the Seathwaite valley is revealed below, as the terrain drops steeply away.

Take care down the steep, faint path, which leads to the left of the Hanging Stone then descends a steep gully piercing the crags. It’s a hands-on affair to negotiate the rocks near the bottom, especially as they may be damp and slippery.

We now thread our way through the boulder field to join the main path from Gillercomb to Sourmilk Gill.

Picture, above, shows Seathwaite from the top of Sourmilk Gill

The route has a sting in the tail. Just as we think we’re almost home and dry, the gill throws various minor scrambles at us as we descend towards the farm past the Seathwaite Slabs before reaching the valley bottom, with aching thighs and knees, grazed hands but an immense satisfaction at paying homage to one of Lakeland’s finest peaks.